Tell It Again #8: Benegal and Dubey, Part 2

Welcome to ‘Tell It Again’, a newsletter that dives into the life and work of Girish Karnad.

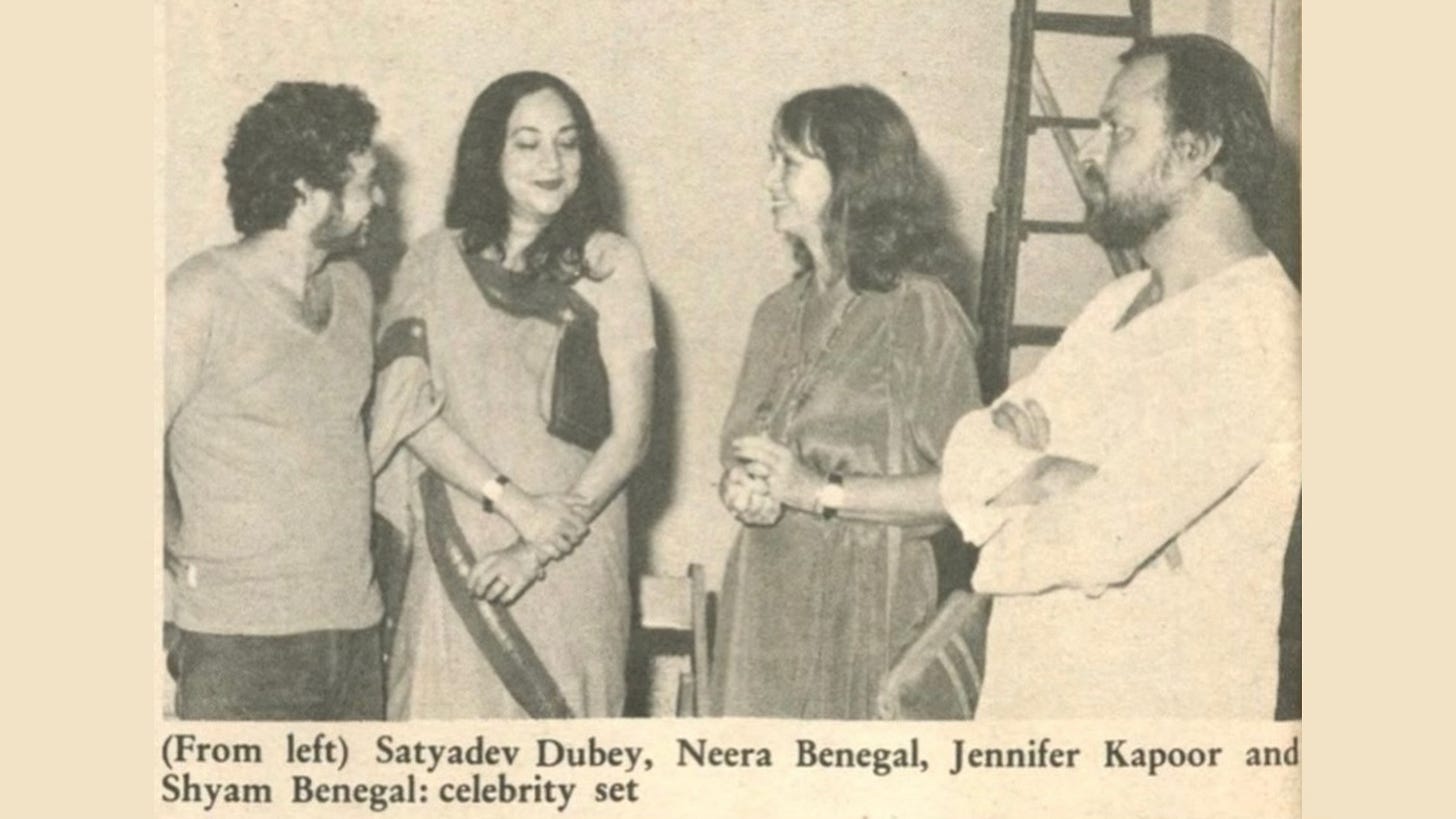

Our theme continued into this week: the friendships and creative networks around Girish Karnad, Shyam Benegal and Satyadev Dubey. In Part 1, we took you through the Karnad-Benegal-Dubey trio’s work in film; today, the saga continues on stage.

For all his work in film, the theatre remained Karnad’s first love. The same was true for his friend, the writer, director, teacher and irrepressible cultural force, Satyadev Dubey. Dubey was the director who had discovered Dharamvir Bharati’s epochal Andha Yug. He was passionate about Indian languages and, until later in his life, sceptical about Indians writing in English.

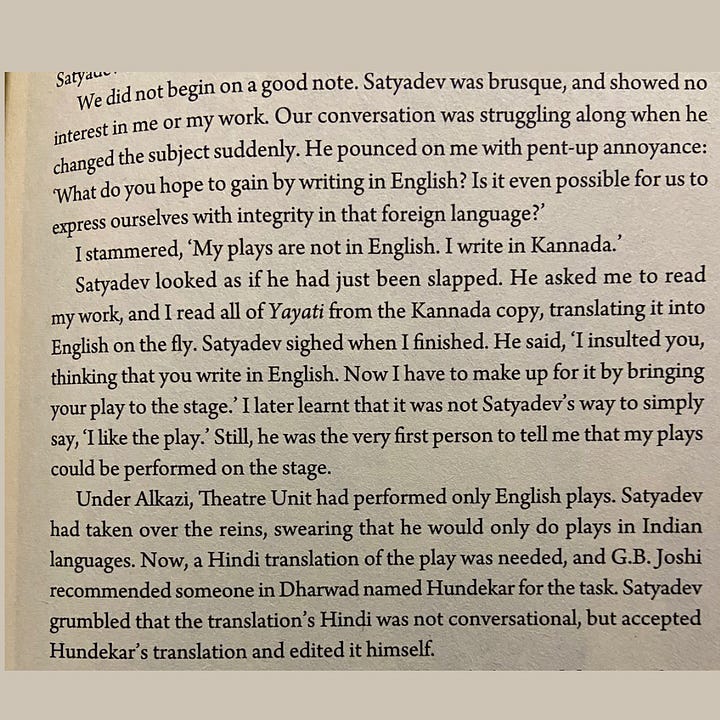

He first met Karnad in 1965, and each of them would remember the meeting quite differently:

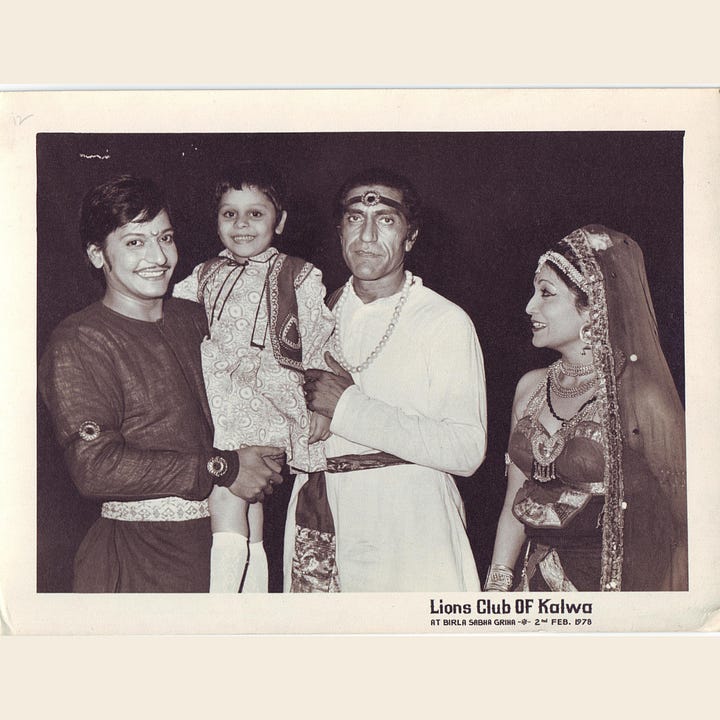

Either way, Dubey was one of the first directors to take on Yayati, starring his protégé Amrish Puri.

Punctuated by rounds of drinking, sparring and reconciliation, the Karnad x Dubey bond grew over the decades, through productions of Hayavadana, then Bali (with Naseeruddin and Ratna Pathak Shah) and later in both their lives, Dubey’s adaptation of Wedding Album.

“The first woman in Indian theatre to express her sexuality”: This was how Dubey saw Padmini, the female protagonist of Hayavadana. In 1970, Dubey directed the play with Amol Palekar and Amrish Puri in the lead male roles, and Sunila Pradhan as Padmini.

For his staging, he took out all of Padmini’s lines where she offered either explanation or apology for herself — leaving her desires and sexuality bold and unapologetic.

The theatre director Sunil Shanbag recalled that show for us:

“The bare stage with flat lighting and a battered steel folding chair that greeted us at Tejpal auditorium in 1972 didn’t prepare us for the magic to follow...

I was still in school, but home on vacation and that evening remains etched in my memory. I was mesmerised by how the brilliant text, the staging, the music, and the performances created magic on that bare stage. When I left the auditorium my friend nudged me and pointed to a frowning, long haired man in dishevelled clothes and whispered, “That’s Dubey…” As I travelled home in the local train from Grant Road I thought … If this is theatre then this is what I want to do for the rest of my life.”

Dubey considered Hayavadana a high point of his directing career.

“The play, staged almost simultaneously in 1972 by Karanth in Delhi and Dubey in Bombay, was hailed as the beginning of the ‘Theatre of the Roots’ movement in India,” Karnad later wrote, in a chapter intended for his memoir.

Vijay Tendulkar watched Dubey’s show in Bombay, and said to Karnad afterward: “I too want to use folk forms in a play. I’ll sit down to write at once.” The result was Ghashiram Kotwal.

By the 1980s, Dubey and Karnad were tried and tested collaborators. They had worked on Benegal’s films, and written Bhumika together. Dubey said that he now just “assumed that if Girish had written a play, I had automatic rights over it” – which caused major confusion when, in 1988, he launched into staging Nagamandala, even though Karnad had given the rights to Vijaya Mehta.

Writing from Chicago, Karnad tried to make his friend see reason. Dubey refused. “This is a trial of strength,” he wrote back. “Try stopping me. I am not logical — I am Satyadev Dubey.”

(See photos of Mehta’s production here, or revisit our newsletter about the memorable early productions of Nagamandala.)

Dubey’s plans to direct Bali, with Naseeruddin and Ratna Pathak Shah — playing the King and Queen respectively — grew so protracted that he eventually had to ask if everyone still wanted to do it.

Karnad thought they should cancel. Pathak Shah didn’t love the play, but thought the role was a good one. The question was settled after Shah rang, and said: “Dubeyji... how badly can we do it?”

(Much later, the Shahs would return to perform Bali, much happier in their new roles as the Mahout and the Queen Mother this time, directed by Nona Sheppard at the Leicester Haymarket Theatre in the UK. More on that here.)

One of their final collaborations was Dubey’s Marathi production of Karnad’s Wedding Album, titled Sapadlelya Atahvani. It opened alongside Lillete Dubey’s long-running production in English.

Dubey had a rare power over Karnad – to criticise his work, and to edit him however he felt necessary.

In Satyadev Dubey: A Fifty-year Journey Through Theatre, a volume edited by Shanta Gokhale, Dubey talks about watching Lillete Dubey’s English show: “I saw first and foremost what are the things I had to throw out and I threw them out.”

He thought the play was full of problems; above all that Karnad was doing too much. He was “trying to encompass the entire world,” while using the intimate material of his own family stories. “The thing spread itself out so broadly that nothing remained.”

“So I concentrated on the family, the mother, the two daughters — the father like all men was not important.”

It did not go down well with Karnad: “I was hopping mad. Wedding Album is about a family. Dubey hadn’t a clue about family life. It was harrowing for me to see what was being passed off as my play.” He also added that Dubey “knew I was upset but I never spoke to him about it. And, it never came in the way of our relationship.”

Otherwise, Karnad regarded Dubey as a director loyal, above all else, to the text. So when Dubey asked him for rewrites, sometimes even going back and forth between versions, Karnad obeyed.

“[Dubey] calls me not India’s very good playwright,” he later said, “But a very good rewriter.”

This newsletter and the Instagram and Facebook pages it is tied to are part of an open archive of Girish Karnad’s life and work conceived by Raghu and Chaitanya as a way to keep his wide legacy alive and in public view. Its curator is Harismita.