Welcome to ‘Tell It Again’, a newsletter that dives into the life and work of Girish Karnad. Our title is from an opening line in Nagamandala:

“You can't just listen to the story and leave it at that. You must tell it again to someone else.”

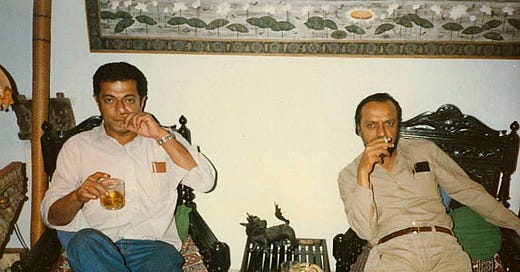

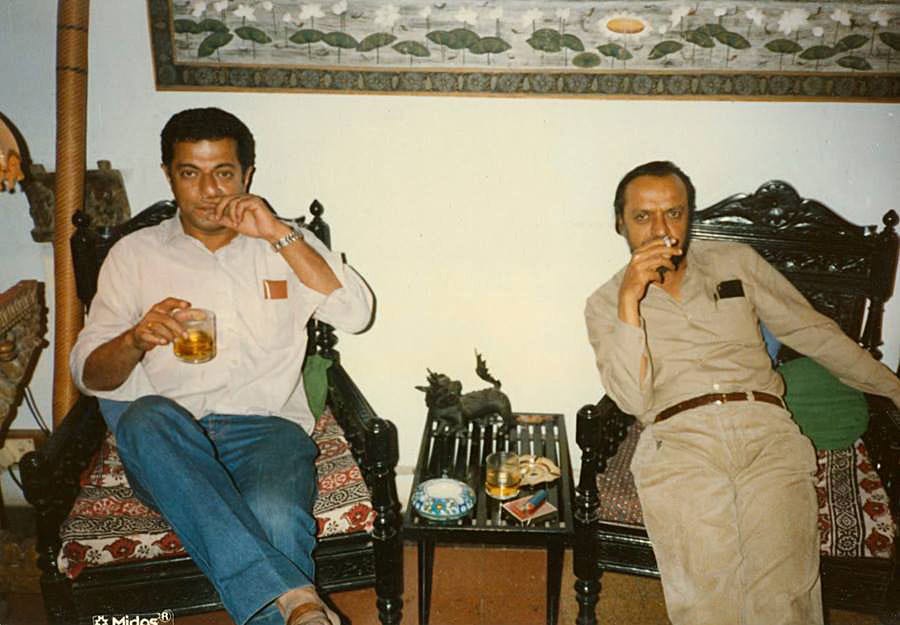

This week, we travel back to the 1970s, to Pune and Bombay, where Girish Karnad and a set of youngish writers, actors, and artists drank, quarrelled, and created a new style in cinema and on stage. The trio at the centre of this creative network were Karnad, Shyam Benegal and Satyadev Dubey.

In his college years in Dharwad, Karnad’s closest friend was Krishna Basrur, or ‘Kitti’. Basrur’s iconoclasm, his relative sophistication and his love of writing were magnetic to the young Karnad.

Basrur had a cousin in Bombay: a filmmaker named Shyam Benegal. Kitti would tell Benegal about his long-time friend, and eventually the three met in Bombay. They began hanging out, meeting over tea and samosas near Colaba Causeway, then drinking together into the night. Kitti “was a very imaginative, wonderful fellow. We used to love him on the unit,” Benegal told us. “When he got drunk, he was unruly as hell... and he was unreformable."

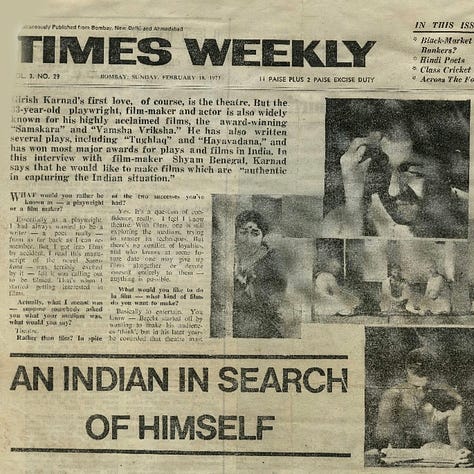

Before they ever worked together, Benegal was so intrigued by Karnad — and Karnad’s own early films made in Kannada — that he interviewed him for a 1973 cover story of the Times Weekly.

Benegal and Karnad also formed a trio with another force of nature, Satyadev Dubey, a writer, teacher and stage director.

Dubey had begun his career acting with Ebrahim Alkazi’s Theatre Unit. He took over in the early 60s, when Alkazi moved to Delhi to establish the National School of Drama.

Their Bombay was a heady scene of writing, rehearsals, affairs, arguments and reconciliations. Dubey’s space at Walchand Terrace — a gift from the industrialist Vinod Doshi — was at the heart of it. It buzzed with rehearsals in the day, and at night it filled with talk and drinking, and a row of mattresses laid out for anyone needing a place to sleep. It was a place where, as Karnad often recalled, you could fall asleep next to a great writer, and wake up next to a different great writer in the morning. He dedicated his play Anju Mallige to Walchand Terrace.

As Benegal told us:

“It was a very alive period, even for me. Dubey [and Karnad], when they were both not drunk, they would be at each other's throats. Then they would get drunk, and it would become a right royal fight... Then you'd find them in the morning, fast asleep next to each other.”

Along with Dubey, Karnad would be integral to three of Benegal’s films — Nishant, Manthan, and Bhumika — which came to define that moment in Bombay’s parallel cinema.

That particular milieu had its own “brat pack”: writers, artists and actors who populated its films, again and again, in shifting combinations: art director and writer Shama Zaidi, cinematographer Govind Nihalani and music director Vanraj Bhatia among them. Most of the actors had their film debuts in Benegal’s early classics, which were all co-written by Dubey. Some, like Anant Nag, Amrish Puri and Amol Palekar, had been Dubey’s students or discoveries in Bombay. Others, like Shabana Azmi and Om Puri, had come from the Film and Television Institute of India, in Pune, or like Smita Patil, had hung out on its campus.

Karnad had his own stint at FTII: at the age of 35, he was appointed the institute’s director. There he ran into two actors: one his immediate friend, and the other, at first, his adversary.

When Karnad arrived in Pune in January of 1974, to begin his term at the Institute, his first friend in the city was a postgraduate lecturer in psychiatry, a young man named Mohan Agashe.

Agashe would visit FTII three or four evenings a week, riding up on a Vespa he had borrowed from Karnad. “Best days of my life,” he told us.

“Arriving on a scooter that belonged to the director of FTII; watching Bresson, Kurosawa, whichever film he had chosen to screen; drinking his whisky, eating food cooked by his mother.”

“Unlike the others,” Mohan Agashe said, “my friendship with Girish was never professional.”

It was a turbulent year for theatre in Pune, and Agashe was right in the middle of it. Vijay Tendulkar’s play Ghashiram Kotwal had set off a storm of controversy, offending some Maharashtrian Brahmins with its frank view of history, caste and the exploitation of women in the Peshwa regime. The producers were forced to cancel the shows.

When the actors (mostly medical graduates, like Agashe) pulled together to stage it on their own, Karnad offered them the auditorium at FTII. The shows sold out, which helped to catapult the play to its eventual legendary status — and to seal Agashe’s lifelong friendship with Karnad.

On campus, however, Karnad was looking at trouble. The face of that trouble belonged to a young actor named Naseeruddin Shah.

This was the issue: at the institute, direction students completed their program by filming a short feature. The technical personnel on those shoots — think cameramen, recordists, editors — had to be drawn from FTII departments. There was no such rule for actors. “There were actually students of acting who went through their two years without once facing a camera,” Shah later wrote in his memoirs, And Then One Day, adding: “it stank.”

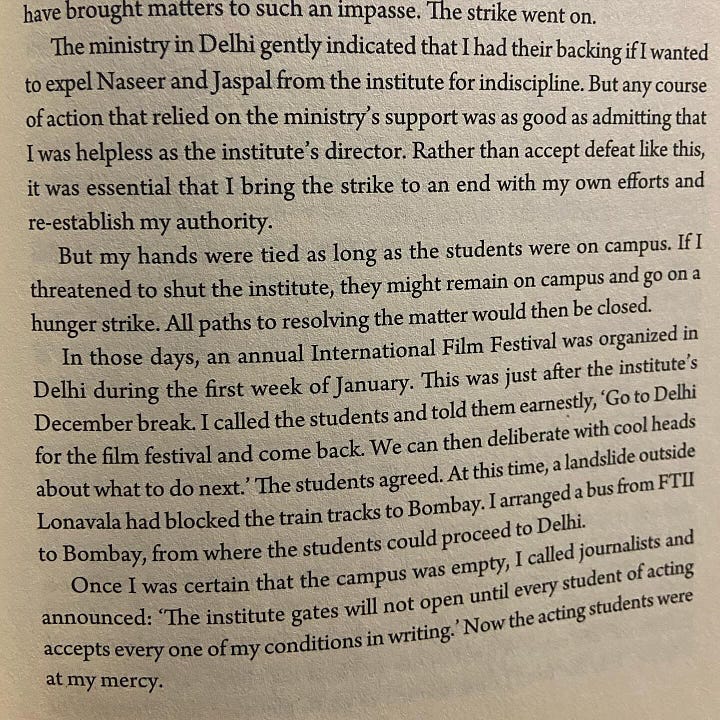

The actors’ protest built up into a hunger strike, and a furious confrontation — one that “created lasting animosities, and a heartburn that hasn’t yet subsided.” Both Karnad and Shah relived the FTII strike in their memoirs, published four decades later.

Here’s Shah in his memoir:

Karnad, in his memoirs, This Life At Play:

After the strike, those “lasting animosities” might have persisted between them. Instead, Shah wrote:

“Surprise Number 3 was a summons to Girish’s office whence I proceeded with some trepidation, to be informed by him that he had been sufficiently moved by my performance in Zoo Story to mention it to Shyam Benegal who right then was casting for his second film.”

Shah went to Bombay to meet Benegal, barely believing he would get the part in the film. Benegal “assured me that I seemed right for the part age-wise,” Shah later wrote, “Besides Girish thought highly of me and he felt more or less certain about me.”

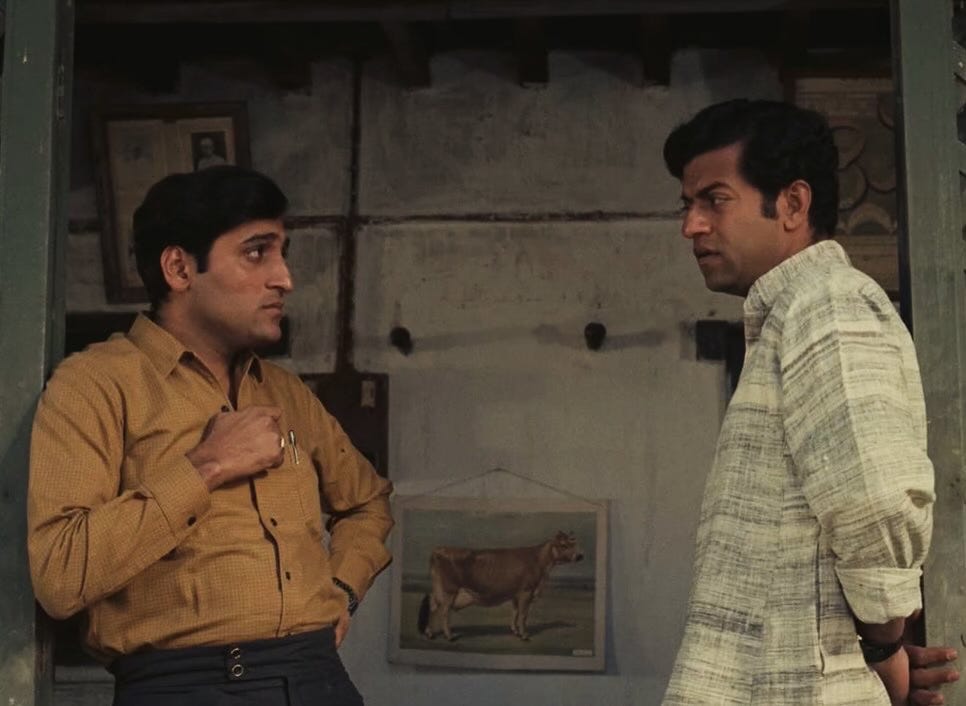

Nishant (1975) was Shah’s first film, the debut Hindi film for Karnad, and an early film role for Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil, Amrish Puri and Kulbhushan Kharbanda. The film was co-written by Vijay Tendulkar and Dubey. It also had a cameo with Kitti Basrur (read our Instagram post on him here), who in the ad hoc style of the era, also ended up credited as assistant director and still photographer.

For Karnad, Nishant established a character type he would play through this era: the mild, even meek, modern Indian gentleman who runs into forces outside his control — above all, feudal patriarchy — and bent on defeating his best intentions.

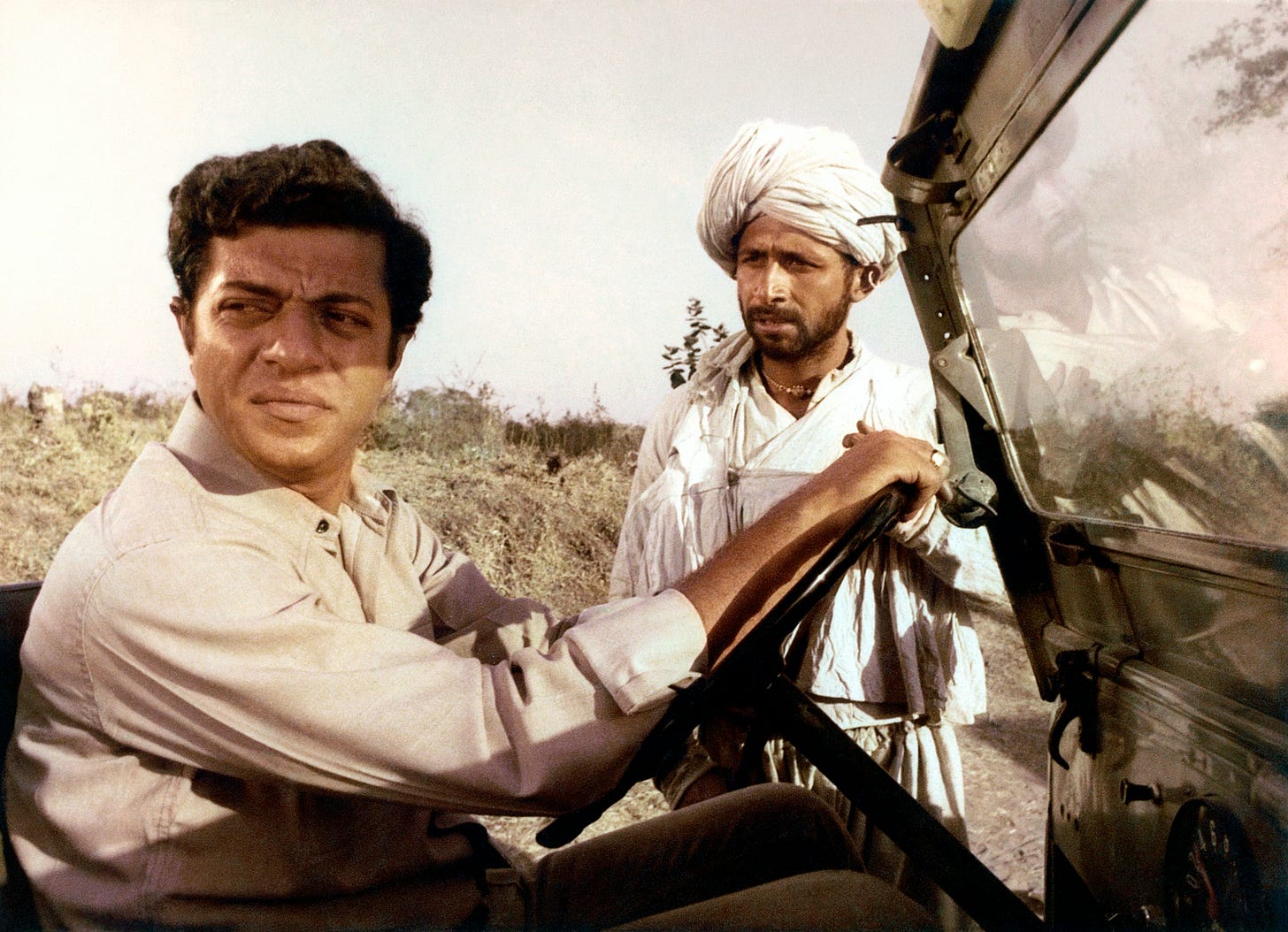

Manthan (1976) boasted many of the usual suspects, and was also written by Tendulkar, this time along with Kaifi Azmi and Benegal, with Karnad’s involvement.

Manthan’s funding is something of a legend in Indian film history: it was the country’s first film to be completely crowdfunded. Five lakh dairy farmers in Gujarat came together to contribute two rupees each, producing a film with a piercing take on caste and class power and the uneven alliances between subaltern and elite benefactors. The very first frame of the film thus reads:

Manthan was recently restored in 4K by the Film Heritage Foundation and this June, it reopened in theatres across India for a weekend — nearly fifty years after its original release. Read about the film’s globetrotting adventures this year here.

On taking advantage of Karnad as a writer, Benegal told us:

“I had taken him as an actor. But he wouldn’t get out of your hair, and since he was there, and was himself a playwright, he understood ... how to develop a character. He could assume many different points of view. That kind of thing Girish was first-class at. I always valued that — because when he’s acting with you, you have him captive.”

For Bhumika (1977), which was set in a Marathi-speaking milieu, Benegal asked Karnad to come on officially as a co-writer with himself and Dubey. Their script won the National Award for the Best Screenplay. Smita Patil, the star of the film, won that year’s award for Best Actress.

Coming up next: part 2 of our newsletter on the Karnad-Benegal-Dubey trio.

This newsletter and the Instagram and Facebook pages it is tied to are part of an open archive of Girish Karnad’s life and work conceived by Raghu and Chaitanya as a way to keep his wide legacy alive and in public view. Its curator is Harismita.

It's so absorbing I wish it hadn't ended.

As for This Life at Play, it's an un-put-downable book. Salaams to Karnad - the one and only!!!