Tell It Again #4: Nagamandala

“Queen of the long tresses. For when her hair was tied up in a knot, it was as though a black King Cobra lay curled on the nape of her neck, coil upon glistening coil.”

— Story, Nagamandala

A warm invitation from all of us at Tell It Again. Come one, come all to listen to the tale of Rani, for our theme this week is Girish Karnad’s Nagamandala.

Padmavati (Pinty) Rao recalls an evening working on Malgudi Days in the mid-1980s. She was winding down on set with Girish Karnad and Shankar Nag:

“On a Saturday night, on the steps of a rented cottage under a star-laden sky… there was Girish, telling us the story of Nagamandala.

It was a folktale that AK Ramanujan had told him and Kambar. Everything about that evening in my memory is surreal. He for some reason was standing while we, Shankar and I, sat on the steps with our folks from [Malgudi Days]. … Girish’s voice pierced the night sky and prevailed over the sound of wild nocturnal life in Agumbe…

Long discussions of rituals, reptiles, the paranormal and much else also followed. I haven't experienced a night sky like that ever after, layered with a timeless story in a voice and erudition as rich as his.”

Karnad had heard two folktales from Ramanujan. The first was the tale of ‘A Story and a Song’, suppressed deep inside a woman, fighting to enter the world and be freed. The second, ‘The Serpent Lover’, was about a woman with an uncaring husband, a man constantly preoccupied by his mistress. She receives a magic love potion, but ends up feeding it to a snake.

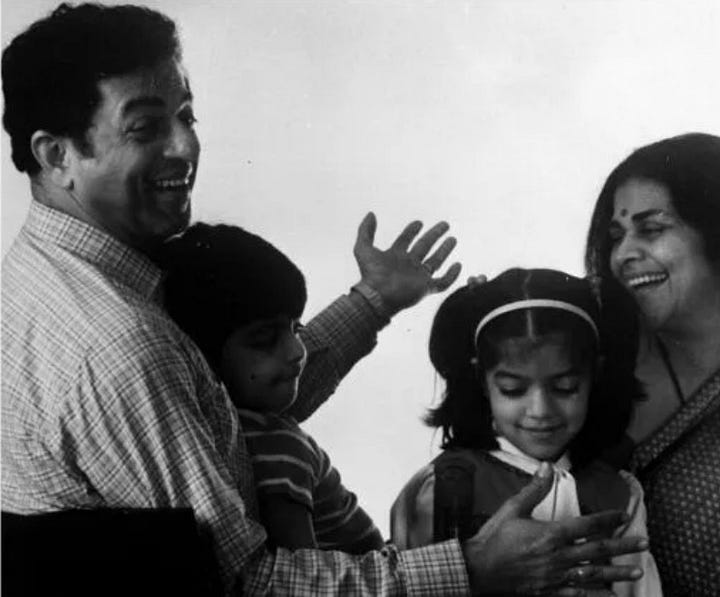

In 1987, Karnad was offered an appointment at the University of Chicago, along with Fulbright funding. He would join the faculty of South Asian Languages and Civilizations, where AK Ramanujan was a professor, and get a break from acting jobs and the film industry.

The family moved to Chicago for a year. Karnad was overjoyed with his time there. He later told SPAN that it gave him “time to read Bharata’s Natya Sastra in detail, to clarify my thoughts on classical Indian theater and poetics by giving a course on the subject for two quarters, spend hours chatting with the research students and teachers such as Ed Dimmock… and finally spend almost every evening, for 10 months, at home with my family—something my profession doesn’t allow me in India.”

He taught for one quarter, and with the encouragement of the department chair, CM Naim, he spent the next one writing and directing a new play. In this play, he combined the two fables that had already captured his imagination and dedicated it to AK Ramanujan: “friend, guru, hero.”

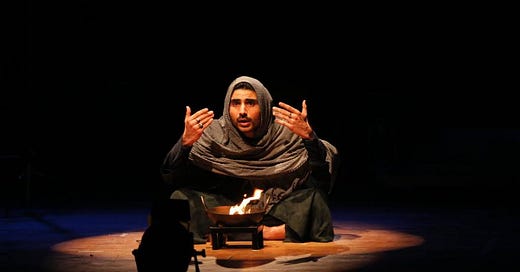

Nagamandala, or ‘Play with a Cobra’ was premiered by the University Theater student company in May 1988. Karnad directed it himself. Working with students in Chicago was a vital part of his fine-tuning the script, he later said. Perhaps as a consequence, it would become his most popular play by far outside of India.

“That Nagamandala was done in so many languages gave him much joy,” Pinty Rao told us. “He was able to give directors all the freedom of interpretation they wanted.” In this edition of the newsletter, we revisit five of the earliest and most memorable interpretations – productions that helped place ‘Play with a Cobra’ in the canon of Indian theatre and stagecraft.

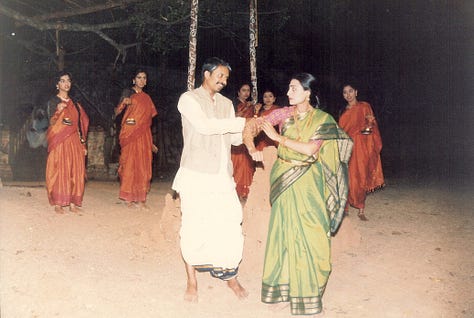

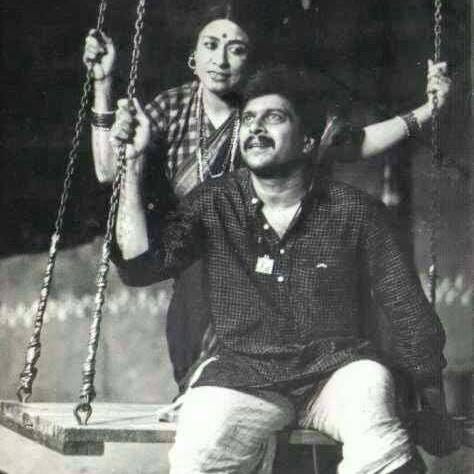

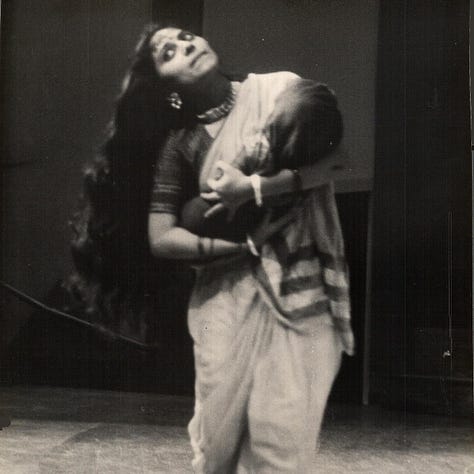

The play’s premiere in Kannada in 1989 was directed by Shankar Nag. Pinty herself played Rani in the first five shows, and her sister Arundathi Nag played Kathe (the Story). In the next five shows, the sisters swapped roles.

Pinty told us:

“The shows were performed outdoors at Chitra Kala Parishad in Bangalore. Mattresses were hired for audiences to be seated on. However, when the shows went full, we even had people sitting on the huge trees out there.

Once, there were people who had come from out of town and could not get seats; so we did an extra show on the same day — impromptu, with no publicity — which also ended up being full. We had used puppets for the snake and the dog which were handled by puppeteers on a concealed catwalk. That was where they swung the lit lamps from — which had to have mustard oil so they would not go off in the wind.”

The cast included B. Jayashri, Ramesh Bhat, and Shankar Nag himself. It was scored by C. Ashwath, with a spectacular song, “Maayada Manada Bhara” written by Gopal Vajpeyi. Listen to a rendition of the song by Pallavi MD here.

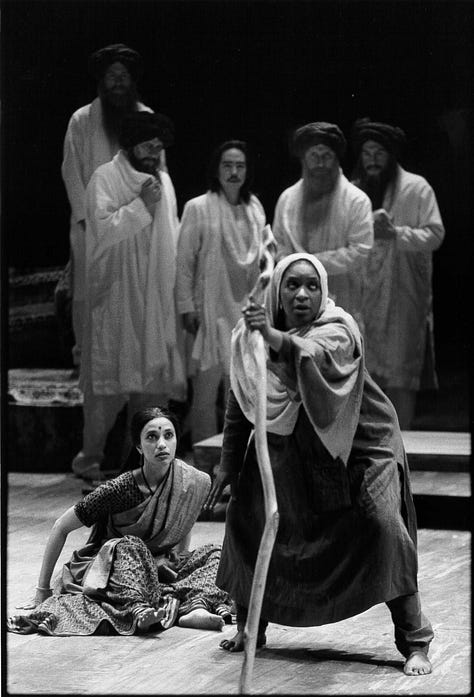

In New Delhi, meanwhile, Neelam Mansingh Chowdhry was creating a production in Punjabi that she would breathe life into again and again over the next three decades.

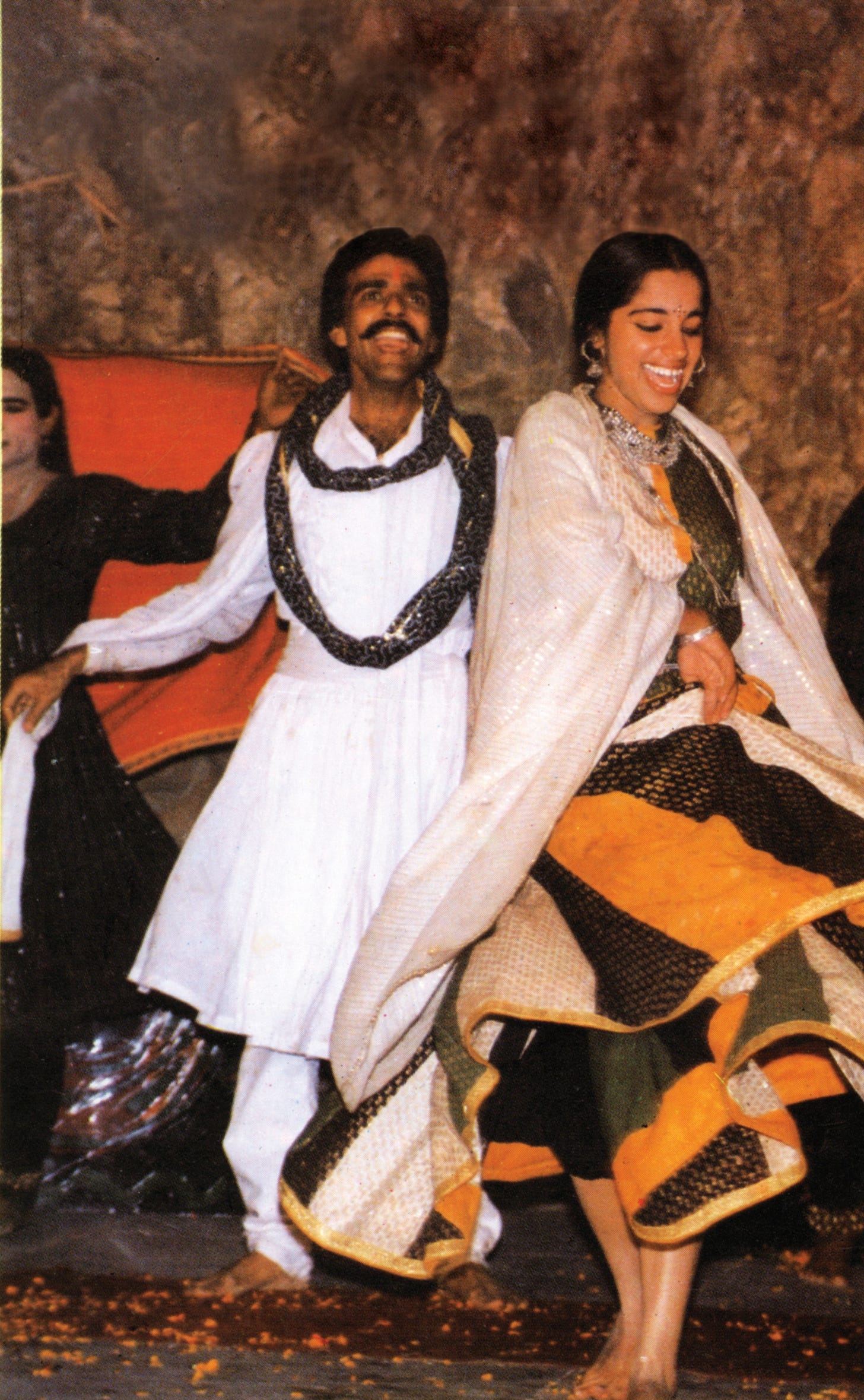

Naga Chhaya (1990) drew on the naqqal folk tradition, casting a mix of its performers alongside city-based actors. The play was translated by the eminent poet Surjit Patar, and scored by BV Karanth, using a medley of instruments and vocals unusual for theatre at the time.

Suresh Awasthi, in a review of the play, said:

“‘Naga Chhaya’ represents the best of ‘new’ contemporary theatre, a ‘theatre of roots’ … Watching [it] is seeing a segment of Punjab’s rich traditional performance culture — rhythms, colours, sounds, designs, gestures and postures. It is like reading a cultural document.”

Karnad watched the Company production at Kamani Theatre, and he loved it. According to Neelam Mansingh, he wanted the play to tour around Karnataka. The Punjabi language show “ended up performing not only in Bangalore and Mysore but also in cities like Udupi, Heggodu and Dharwad to receptive audiences.”

“In 2005, I revisited the play and once again in 2014,” the director wrote, “And each time it spoke to me afresh.” The published edition of Nagamandala, from OUP, still uses pictures from the early shows on its cover.

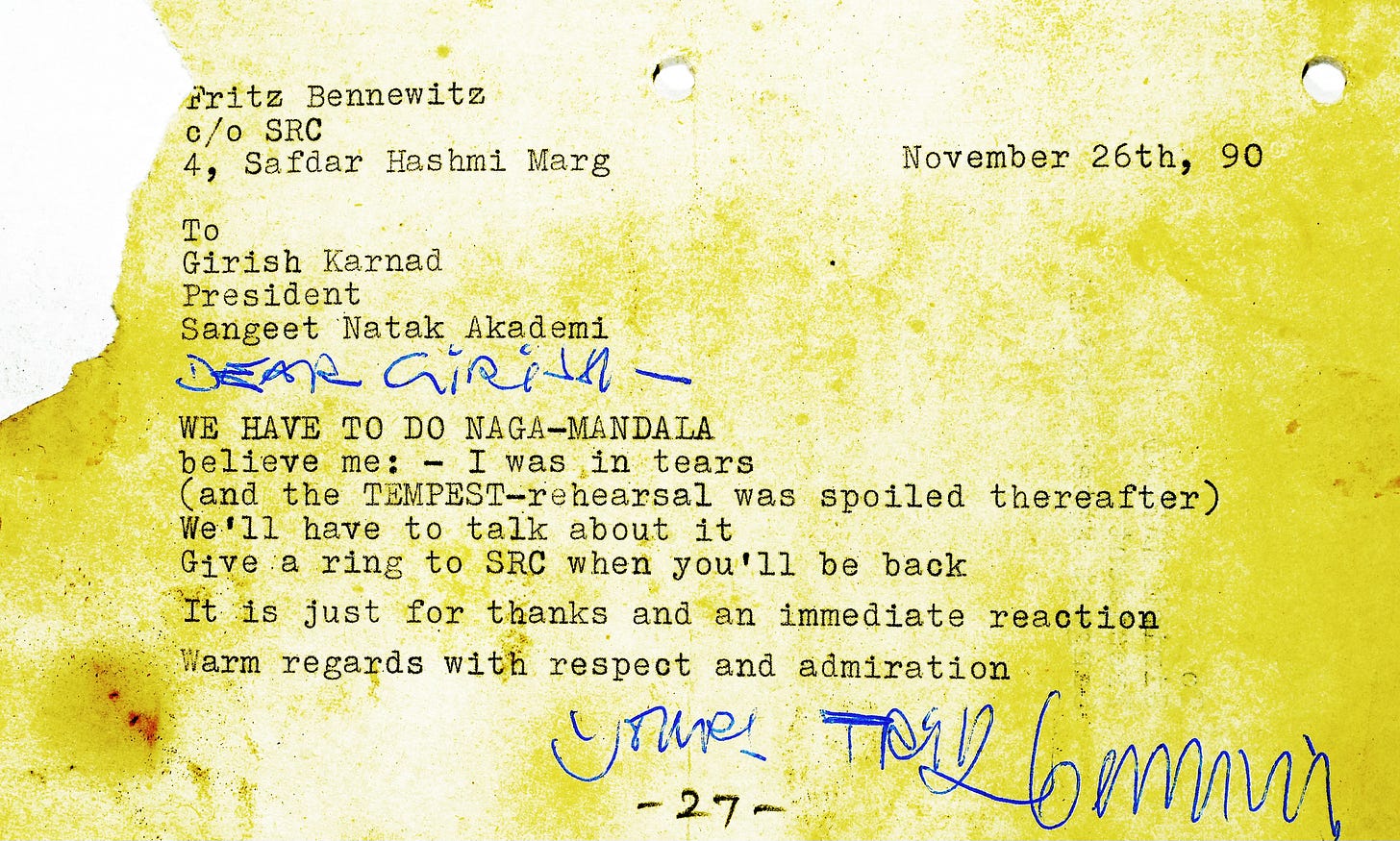

In those years, the German director Fritz Bennewitz was working at Delhi’s Shri Ram Centre. He read the play and fired off a postcard to Karnad: “WE HAVE TO DO NAGA-MANDALA, believe me: — I was in tears.”

Bennewitz, who frequently collaborated with Vijaya Mehta, sent the script to her in Mumbai. Mehta decided to direct a pilot production at the National Centre for Performing Arts, and then to co-direct it with Bennewitz at the upcoming Festival of India in Germany.

The only obstacle was Karnad’s close friend and creative accomplice, Satyadev Dubey. Without ever asking for permission, he had made an announcement to the press: that he would stage Nagamandala in Hindi and English. Karnad had promised Mehta the rights in both languages. This led to a heated exchange of letters (preserved in Karnad’s archives at the Ashoka University).

Dubey, defying calls to see reason, eventually wrote to his friend: “This is a trial of strength. You may side with her if you wish. Try stopping me. I am not logical – I am Satyadev Dubey.”

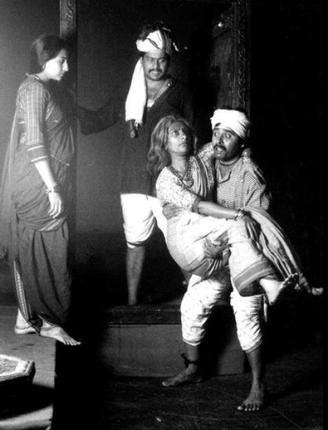

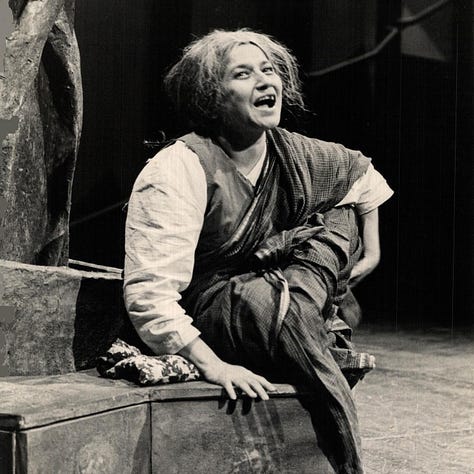

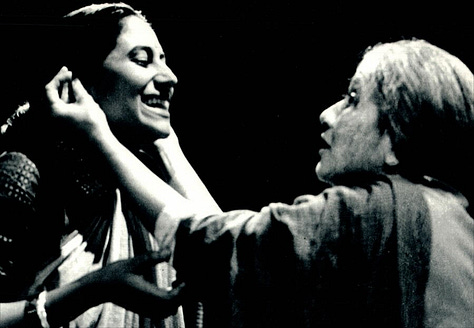

Eventually, Karnad prevailed. In her autobiography Jhimma (2013), Mehta recalled three moments that stunned the audience during her 1991 run. These passages were generously translated for us by Shanta Gokhale.

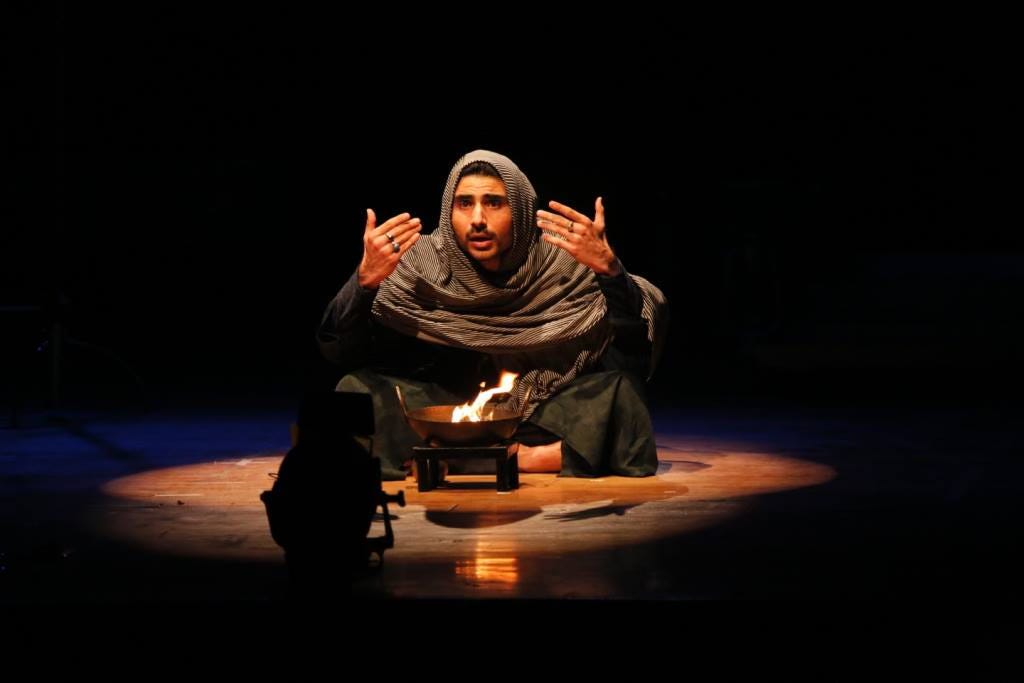

The first moment was the opening scene of the play, as seventy or eighty twinkling oil lamps enter a dark stage. The next was the union of Rani and Nagaraj, “played out against the fervour and beat of an Adivasi song”, as their bodies twisted, turned and wound around each other without touching.

“The third scene that continued to haunt the audience was the Naga-pariksha, ordeal by snake venom. When Rani agreed to face the challenge, a deep, sombre chant of Om began. The collective voice of the villagers gathered around her was like the drone of a strummed tanpura, adding a sense of mystery to the event. The soft thumping of a drum joined in. Rani approached the totem pole, moved forward, recoiled, but then walked back and plunged her hand into the snake hole at the foot of the pole.

Something seemed to be pulling her hand down. She struggled to free it. When she finally managed to pull her hand out, it had turned into the hood of a cobra. She stared fixedly at it. The cobra hood came close to her face, slid around her neck as though to sting her, but caressed her instead, and slowly slithered down her body and disappeared.

By then the chanting and drumming had reached a crescendo. At this point, it stopped. There was a jubilant shout. The villagers hailed Rani as a goddess.”

Mehta’s 1991 production at the NCPA starred Bhakti Barve as Kurudavva, Sukanya Kulkarni as Rani, Sanjay Belose and Ganesh Yadav, and proved a runaway success in Mumbai.

Mehta had already staged Karnad’s Hayavadana in Germany in 1984, and she was now taking Nagamandala to open the theatre segment of the Festival of India in Germany in 1992.

The Leipzig show, though, would turn out quite differently.

“All was not well in East Germany,” Mehta wrote in her memoir. Budgets had been cut, and after the fall of the Wall, actors and musicians had rushed off to Berlin to find work in films and TV. Bhaskar Chandavarkar, accustomed to working with members of the Symphony Orchestra, “was given three musicians… from a little-known jazz band.”

Mehta wrote:

Our first show in Leipzig fell flat on its face. Nobody could be blamed for it. How could people be expected to take an interest in some Indian folk tale when their world was in the midst of a radical political, social and cultural upheaval?

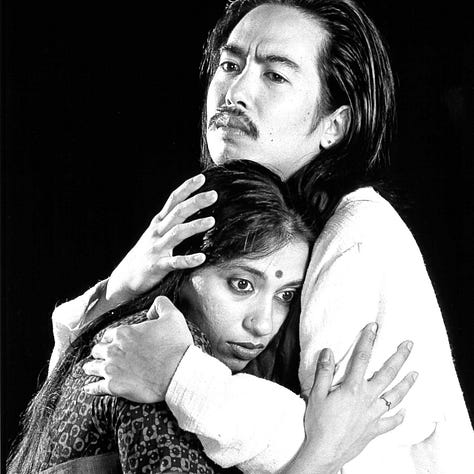

Across the Atlantic Ocean, Nagamandala would become the first contemporary Indian play staged by a major American theatre in 1993: the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis.

During his year in Chicago, Karnad had met Madeline Puzo, who became producing director at the Guthrie, working with artistic director Garland Wright. Wright directed the play as part of the theatre’s thirtieth birthday celebrations, with Stan Egi playing Appanna and Naga, and Isabell Monk as Kurudavva. For the New York Times’ reviewer, the highlight of the play was Nirupama Nityanandan (playing Rani), who gave off “an authentic aura of poetry, crucial to the evening’s success.”

The New York Times didn’t love the Guthrie production. About its folk style, the reviewer said, “a little of this kind of friskiness goes a long way. Two acts’ worth… constitutes a virtual expedition.”

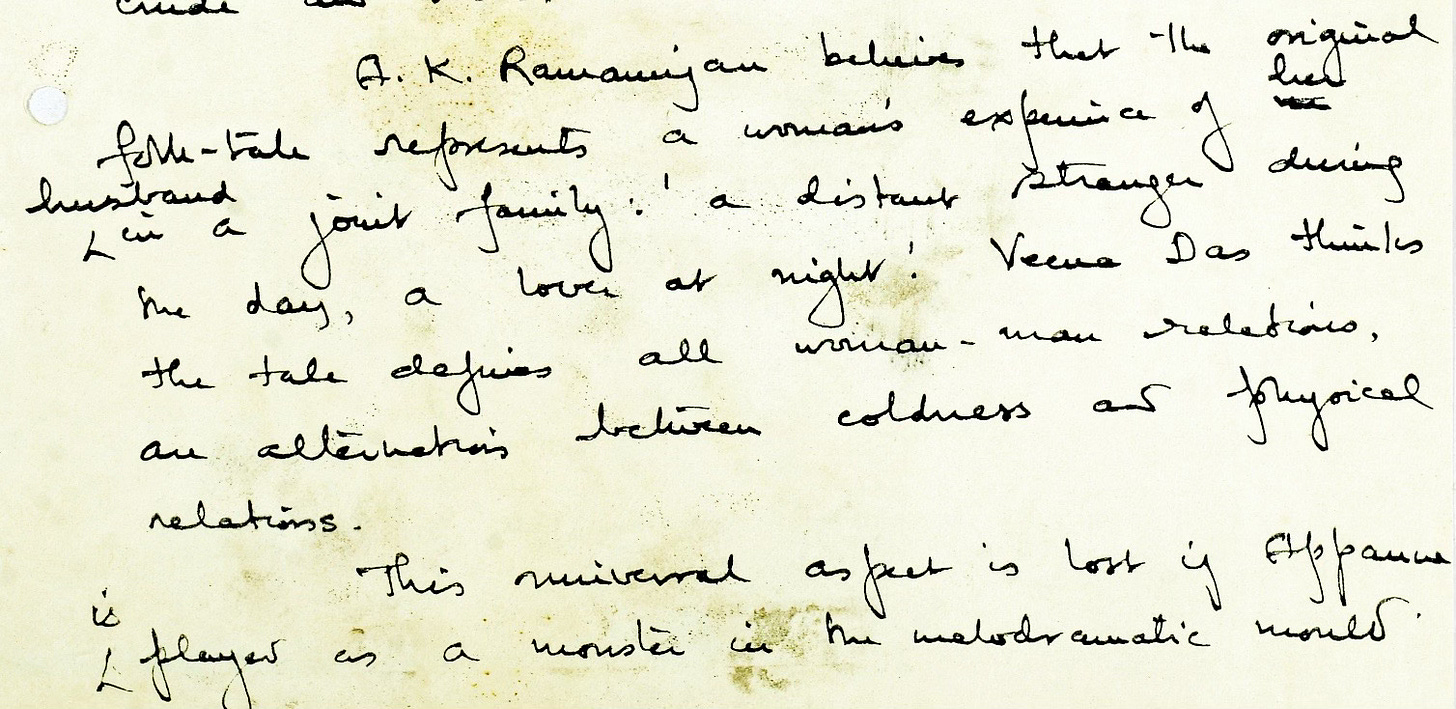

It isn’t hard to watch or read Nagamandala and come away with a view of it as a simple Indian folktale: a magical story with an otherworldly, shape-shifting cobra, an archetypally evil husband, a wise old woman, and a beautiful heroine who triumphs and lives happily ever after. But the play has inspired a rich variety of critical interpretations, drawing on the many ways it has been performed — and the way it centres Rani's emotional needs and sexual desire.

Maya Pandit remarked that Rani’s tender, playful, and sensuous nights with Naga, and her “drab and dull existence when the real husband comes home to eat at day… symbolise the contradiction in women’s life in general.” For Aparna Dharwadkar, Karnad’s play created a world in which a woman’s desire is not just articulated, but is a powerful force that can control fates, and is in itself desired, a “prize for which men willingly or unwillingly sacrifice themselves.” Thus, “Rani moves from a position of total abjection to one of unqualified power.”

Even Rani’s happy ending is open to reinterpretation, both within the text of the play and outside of it. Once, Karnad recalled, he was speaking with the sociologist Veena Das and summed up the conclusion with the traditional phrase: ‘And then Rani gets back her husband and her child and lives happily ever after.’ ‘No, no,’ Das corrected him. ‘She drowns her individuality in her domesticity and becomes a nothing.’

“Come let us flow

down the tresses of time

all light and song.”

This newsletter and the Instagram and Facebook pages it is tied to are part of an open archive of Girish Karnad’s life and work conceived by Raghu and Chaitanya as a way to keep his wide legacy alive and in public view. Its curator is Harismita.