Welcome to ‘Tell It Again’, a newsletter that dives into the life and work of Girish Karnad.

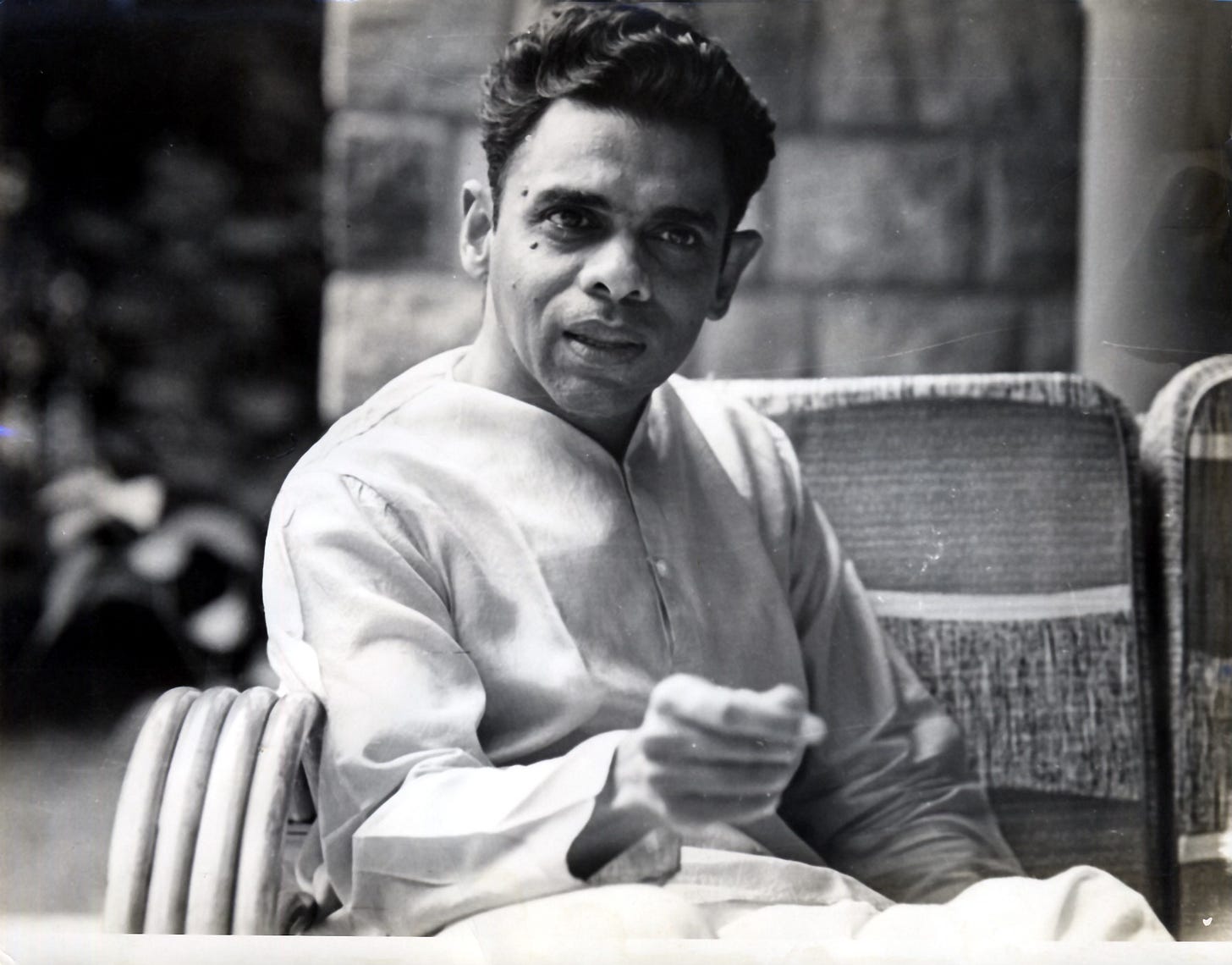

This week, we explore the deep creative debts and long friendship between Girish Karnad and AK Ramanujan.

You’re standing at a train station and waiting with a friend. They’re a fair bit older, feel much wiser, and seem to know about everything under the sun. You’re all admiration toward them, and when they talk, you listen.

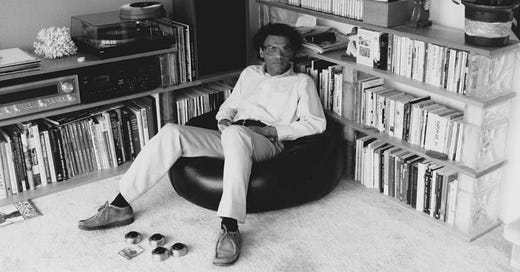

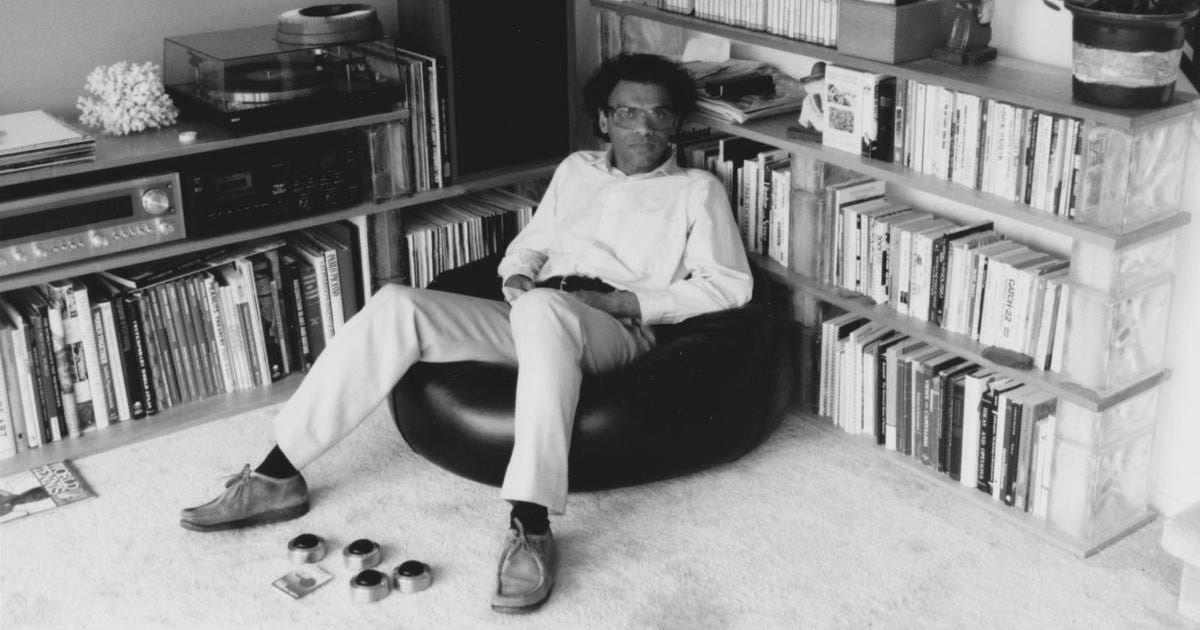

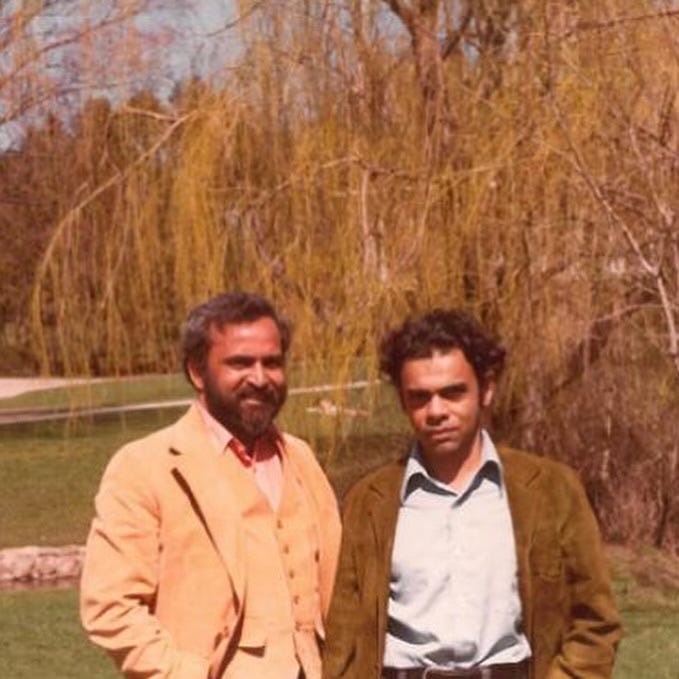

This is roughly how AK Ramanujan and Girish Karnad got on in their early days as friends. Ramanujan was a twenty-seven year old poet and junior lecturer in Belgaum, and Karnad was sixteen, studying in Dharwad. They were separated by age, distance, and disciplines: Karnad studied mathematics, and Ramanujan taught English Literature.

In his memorial lecture, Karnad recalled:

“Regardless of where we met, in restaurants, in parks, on railway platforms or while waiting for the bus, he would deliver impromptu lectures and I listened avidly, and this process continued throughout my life.”

Over the following six decades, too, Ramanujan “turned up with amazing regularity as a source of ideas for my writing.”

The Early Days

Nikhil Krishnan, in a Caravan article analysing Ramanujan’s work, writes:

“The rare confidence of the young Ramanujan lay in how he saw no reason modernist writing could not as well happen in Belgaum as in Bloomsbury.”

Early on, however, it was Karnad who gave a practical boost to Ramanujan’s literary ambitions.

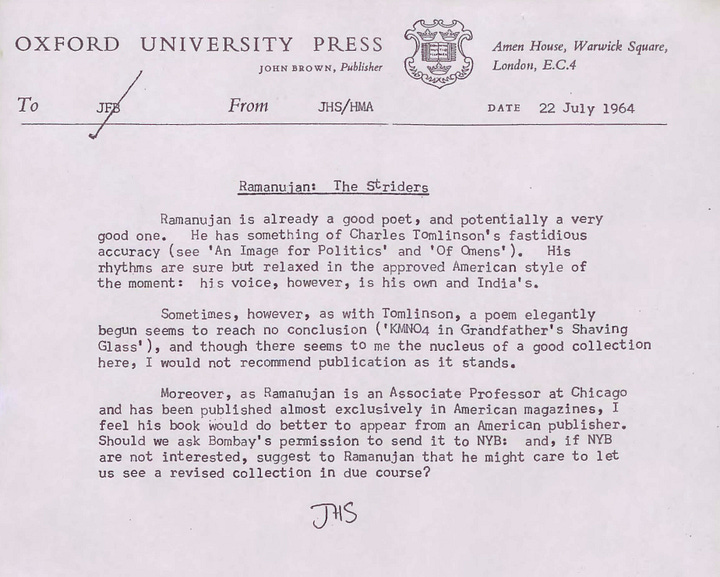

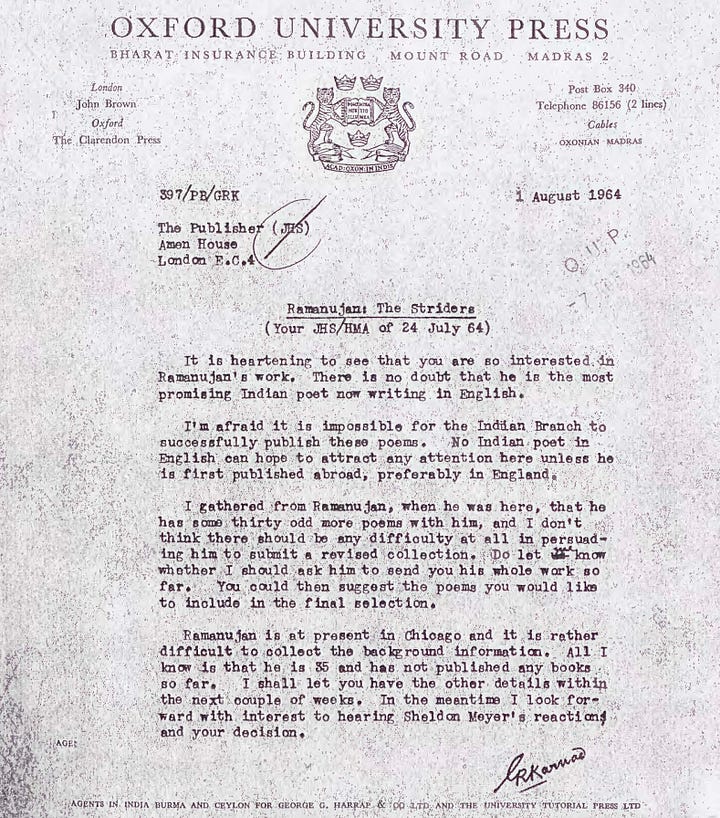

Fresh from a masters at Oxford, Karnad was employed in Madras by the Oxford University Press. He had tried showing his friend’s poetry to Roy Hawkins, the general manager there, but the work was rudely rejected.

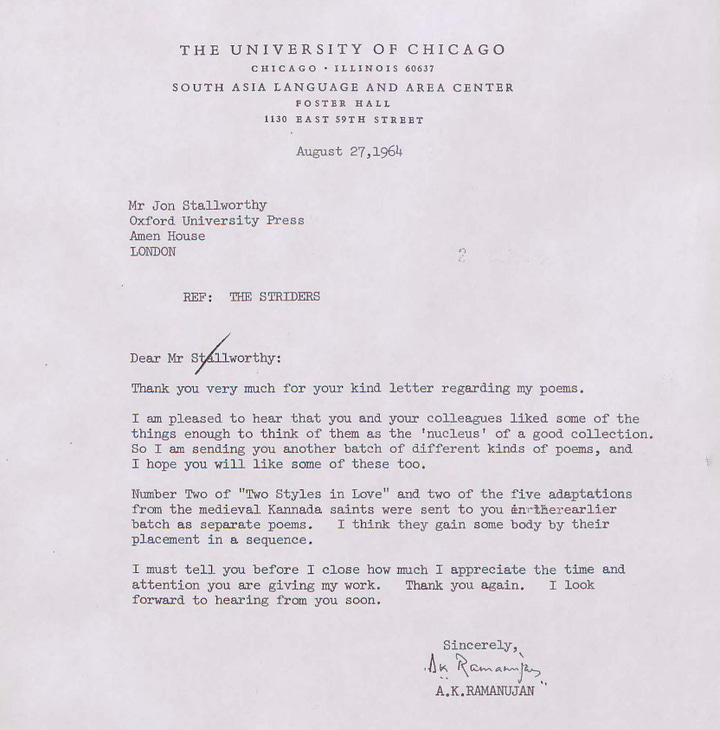

Instead, Karnad posted the poems straight to London, to the eminent Jon Stallworthy, then the editor of the Oxford Poets series.

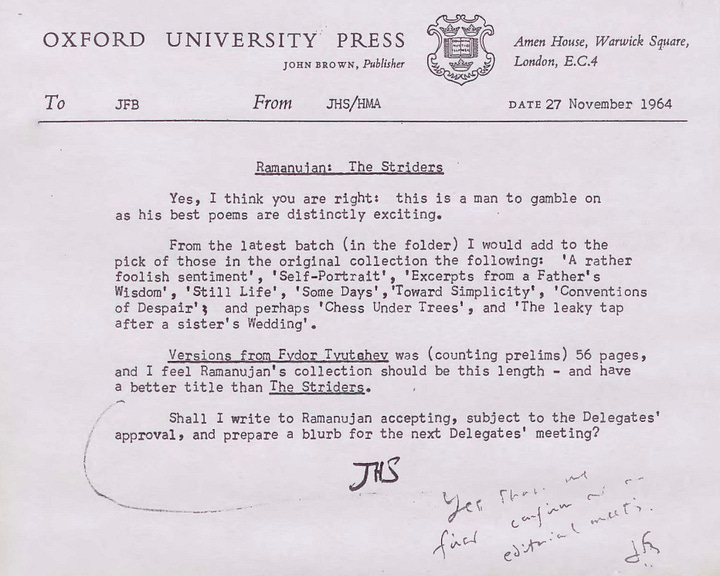

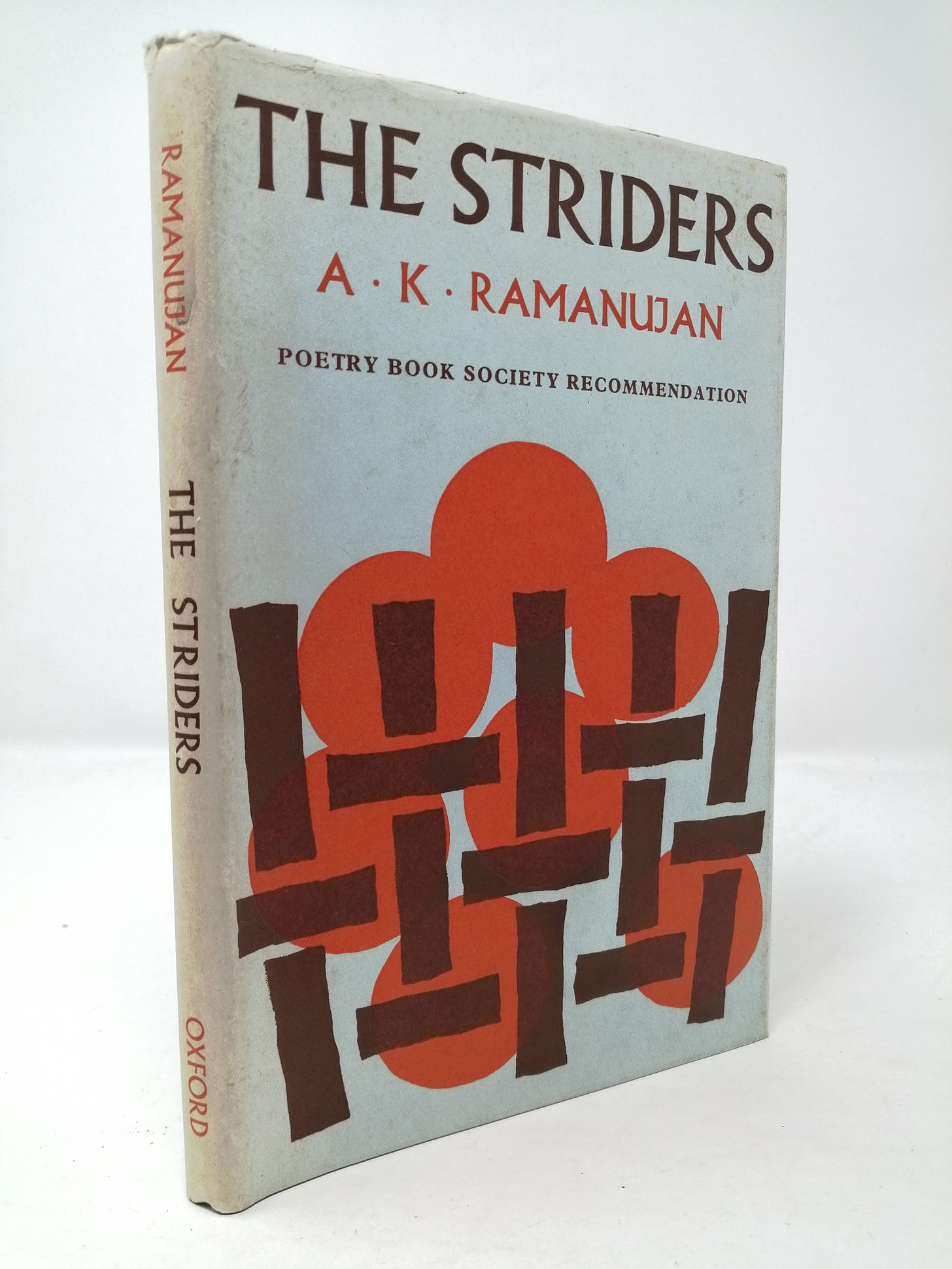

Stallworthy was impressed, and asked to see more. The poet’s voice, Stallworthy said, was “his own and India’s”. Six months later, Ramanujan’s first collection was published by OUP London; a rare achievement for an Indian poet. Karnad recalled:

“Ramanujan wrote to me: ‘This is one of the few events in my life that has made me personally happy.’ (Raman hardly ever used the word ‘happy’ while speaking of himself.)”

The Striders (1966) would be endorsed by the Poetry Book Society in London, and secured him tenure at the University of Chicago, where he would do his most significant work as a scholar and translator. It also included one of Karnad’s own favourite poems by any modern poet, which he knew by heart and remembered for the rest of his life.

Watch Karnad recite ‘Still Another View of Grace’ from the collection at the Bangalore Lit Fest in 2017.

In his 2012 memorial lecture, Karnad said about the poem, which seemed to have been a particular favourite of his:

“I think it is about what happened to him when he left the claustrophobic, segregated and puritanical society in which he was brought up in India, to be launched on a life of sexual freedom, devoid of social constraints but fraught within definable anxieties and fears, in the West.”

Karnad and Ramanujan belonged to a generation of writers still figuring out what Indian writing — and art and literature in their own regions and languages — should look like, what values it should embody. In particular, they were honing a sharp critique of Brahminism, its oppressive neuroses and taboos.

This rebellion found another fine expression in Samskara, a Kannada novel by UR Ananthamurthy. It’s difficult today to grasp the impact Samskara had when it was published. When Karnad first read the novel, he could not sleep. He says in This Life At Play:

“My reading Samskara fundamentally changed the way I saw the Kannada landscape.”

For both Ramanujan and Karnad, the novel was fertile source material in the 1970s. Ramanujan translated Samskara into English, which lifted it into much wider recognition. In US academia, he “championed it… as if it were the only novel to depict a living Hindu culture”, Karnad said.

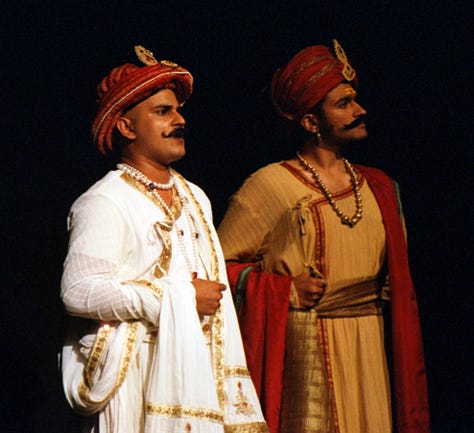

Karnad was jealous of the novel. Heeding Ramanujan’s wisdom — that “translation is a way to take an excellent work written by someone else and make it one’s own” — he made Samskara his own, adapting it into a path-breaking film in 1970. By a stroke of luck, he ended up playing the lead role in the film. His performance as the Brahmin headman, tormented by taboos and temptation, set a new ball rolling in Karnad’s career: as a film actor.

The Folktales

Through the early ’80s, Karnad’s star was rising as an actor and film director. But he despaired at not having any time to write. He had finished his last important play, Hayavadana, in 1971.

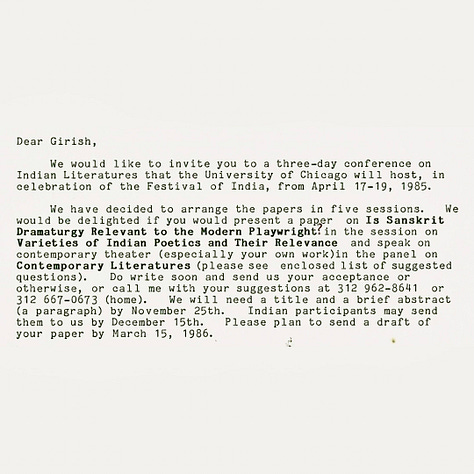

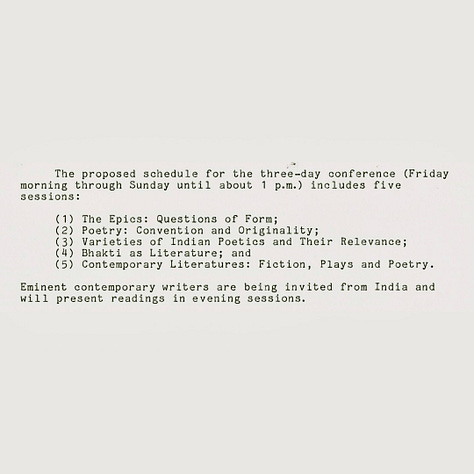

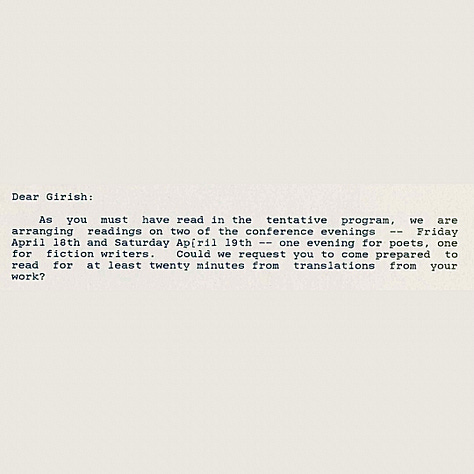

Over in the US, Ramanujan had organised a blockbuster academic event: a three-day conference on Indian Literatures, part of the 1986 Festival of India celebrations at the University of Chicago. The program was full of rising academic stars, including Sheldon Pollock and Wendy Doniger. Nissim Ezekiel attended to read his poems. Karnad was invited too.

What began as a conference lecture in 1986 became the prelude to Karnad’s Fulbright year at the University of Chicago in 1987. In this time — a precious year of thinking, reading and writing — he turned two folk-stories he had heard from Ramanujan into one of his great plays: Nagamandala.

Our last newsletter told the story of how Nagamandala came to be, and of its early productions: you can read it here.

As a young man, Ramanujan had a hobby of collecting folktales. Much later in his life, he published many of these in Folktales from India: A Selection of Oral Tales from Twenty-Two Languages (1992). Reviewing it for the Indian Express, Karnad said,

“My two children, just under twelve, raced through the book: a testimony to the power these tales obviously wield even in the age of Mutant Ninja Turtles... And I have myself in the past shamelessly plundered Ramanujan's collection for plots for my plays and films.”

Ramanujan, generously holding forth as always, told Karnad some of these stories; they went on to form the narrative foundation of a fair bit of Karnad’s work. You might, for instance, read “A Story and a Song” and “The Serpent Lover”, in Ramanujan’s collection of folktales, A Flowering Tree and Other Oral Tales from India (1997), and find the stories from Nagamandala.

From “A Flowering Tree”, his favourite story in the eponymous collection, sprang Karnad’s 1992 film and environmental parable, Cheluvi.

Listen to ‘Bann Aaya Mann Mera’, the iridescent song from Cheluvi sung by Kavita Krishnamurthy here.

The Bhakti Saint-Poets

Among Ramanujan’s more scholarly contributions were his translations of the poetry of the Bhakti saints of South India. These songs and poems were revolutionary in their time: in them, the language of the people, rather than Sanskrit, became the language of devotion. In Speaking of Siva (1973), Ramanujan wrote:

“The poets were not bards or pundits in a court but men and women speaking to men and women. They were of every class, caste and trade; some were outcastes, some illiterate.”

Karnad later observed that:

“bhakti, to Raman, is the last of the great Hindu anti-contextual notions. It defies all contextual structures, caste, ritual, temples, sacred space, sacred time, the Vedas and the Sastras.”

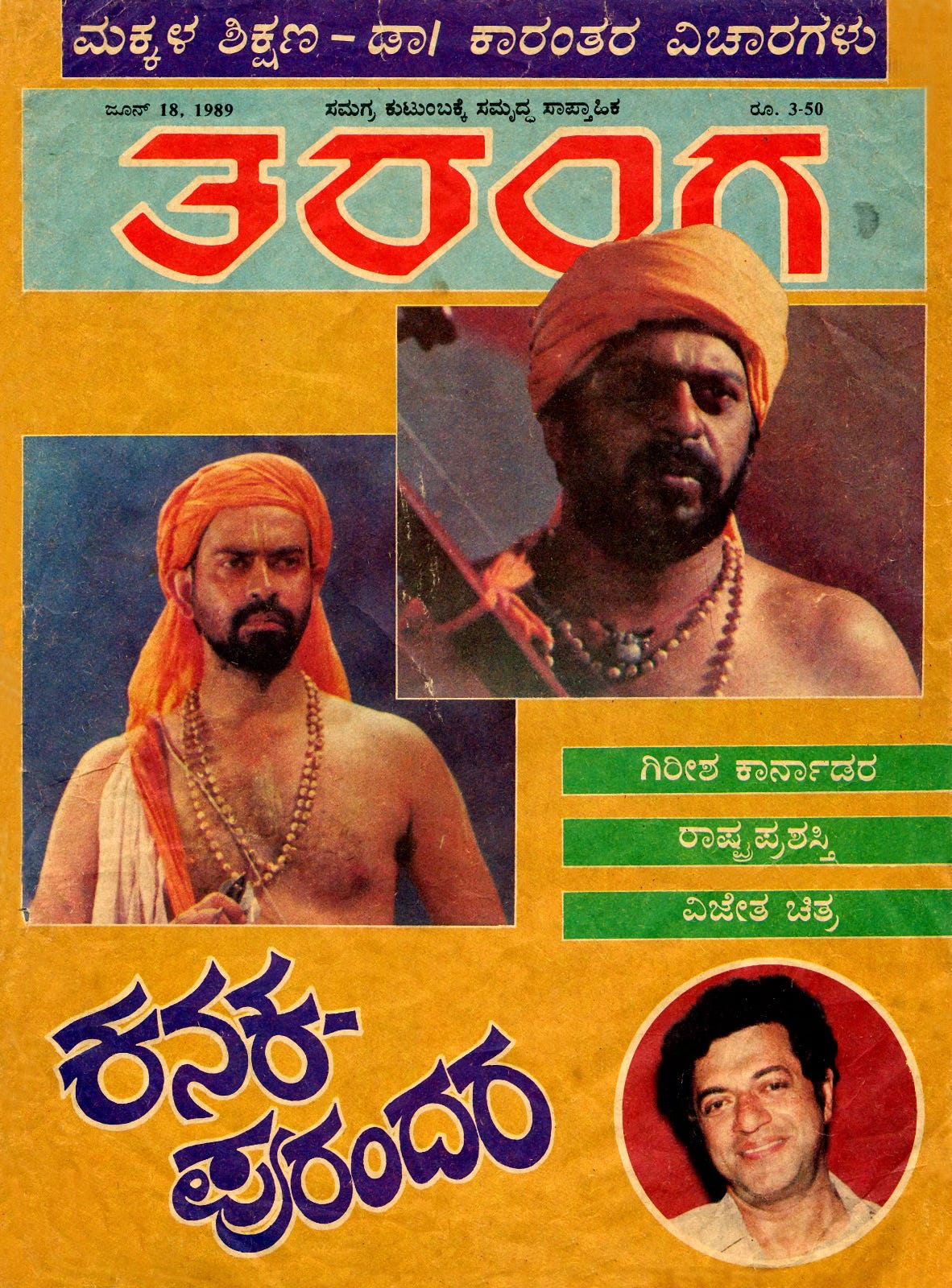

Inspired lyrically and conceptually by Ramanujan’s books, Karnad returned from Chicago and immediately directed a documentary about two Bhakti saints of Karnataka: Purandara Dasa and Kanaka Dasa. Kanaka Purandara was narrated by Tom Alter, and scored by Bhaskar Chandavarkar using Carnatic compositions by the two poet-saints. It won the National Award for Best Non-Feature Film in 1988.

Watch: Kanaka Purandara (1988).

Karnad then launched himself into writing a play about the most celebrated of the Kannada poet-saints: Basavanna, the leader of the radical sharana movement in 12th century Karnataka.

The play, Tale Danda, held a mirror to contemporary politics in India, including the BJP’s rath yatra. Our previous newsletter, on the destruction of the Babri Masjid, revisited the play’s creation and its continued legacy and relevance; you can read it here.

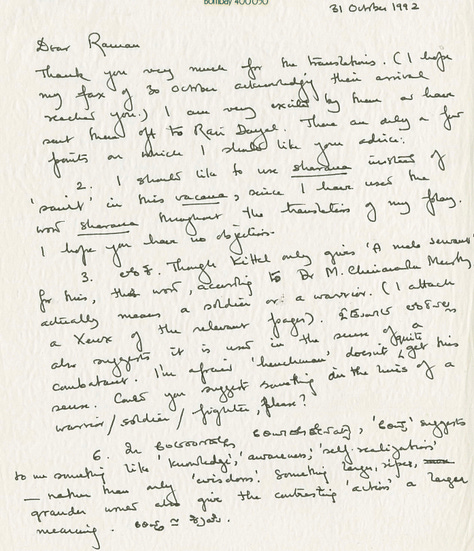

For the English version of Tale Danda, Karnad asked Ramanujan for permission to use vacanas from Speaking of Siva. The vacana tradition encompasses a school of religious lyric poetry in Kannada free verse that was at its zenith between the tenth and twelfth centuries.

Not only did Ramanujan agree to allow Karnad to use verses from Speaking of Siva, he also translated a handful of new ones specifically for the English translation of his play.

Not long after, in 1993, Ramanujan died unexpectedly while under anaesthetic as he was taken into a routine surgery.

Arshia Sattar, then a student of his at Chicago, wrote in an early obituary for the Illustrated Weekly of India:

“Almost single-handedly, he put Tamil studies on the map of American academia and then moved onwards to what has been called the “little tradition” – folklore, folk tales, riddles, proverbs, aphorisms in local languages, ie, the vibrant, living, oral traditions, “literatures without literacy”, he called them. … What Raman has left us... is not vast in terms of volume but each evocative poem, each thoughtful essay, each carefully crafted afterword, each richly resonant paper, which is precious and completely unique, imbued with a genius that was analytic as well as synthetic.”

Resistance

In a decade increasingly poisoned by Hindu radicalism, Karnad’s artistic mandate would change — but it relied as much as ever on his late friend’s ideas.

In 1996, ahead of the 50th anniversary of India’s independence, Karnad was commissioned by the BBC to write a radio play. In a draft chapter intended for his memoirs, Karnad recalled:

“I had been obsessed for many years by Tipu Sultan of Srirangapatna, who had refused to yield an inch to the British, and had died in the battlefield fighting them. In return, the British historians had turned the full force of their malignity to tarring his image.”

It was Ramanujan who had once told him of the diary of Tipu’s dreams – which the Sultan wrote meticulously, come rain, shine, or war. Karnad decided that Tipu “was an ideal subject for the occasion, and radio was the perfect medium to depict his dreams.” The radio play was broadcast in 1997.

Karnad defended Tipu Sultan as a freedom fighter and a traditional hero of Karnataka, defying an increasingly vicious effort to rewrite Tipu as a Muslim fanatic, or simply erase him.

Arundhati Raja, who has directed two other plays by Karnad, also directed the Indian premiere of The Dreams of Tipu Sultan. “He spent a whole morning that stretched into lunch talking to us about Tipu,” she told us, “about the perceptions and feelings of that era and how the play, originally written for BBC Radio, could be transformed onto stage.”

In the play, Raja pointed out,

“we see Tipu not only as the warrior we all know him as, but also as the statesman, the innovator, husband and father.”

Then, fifteen years after his death, Ramanujan himself suddenly became national news as a target of blind reaction and violence. For Karnad, his loyalty to a friend and guru now converged with his calling to oppose Hindutva extremism.

Ramanujan’s 1987 essay, ‘Three Hundred Rāmāyaṇas’ had a simple premise: the Ramayana is not a monolithic text; it’s a widely travelled story that has picked up a rich range of variations across India and Asia. It includes frank descriptions of sex and humour in some variations.

In 2008, the ABVP, a right-wing students’ group, took umbrage at the inclusion of the essay in Delhi University’s history syllabus. They created an uproar, physically attacked the dean of the history department and vandalised his office. The essay was later dropped from the university syllabus.

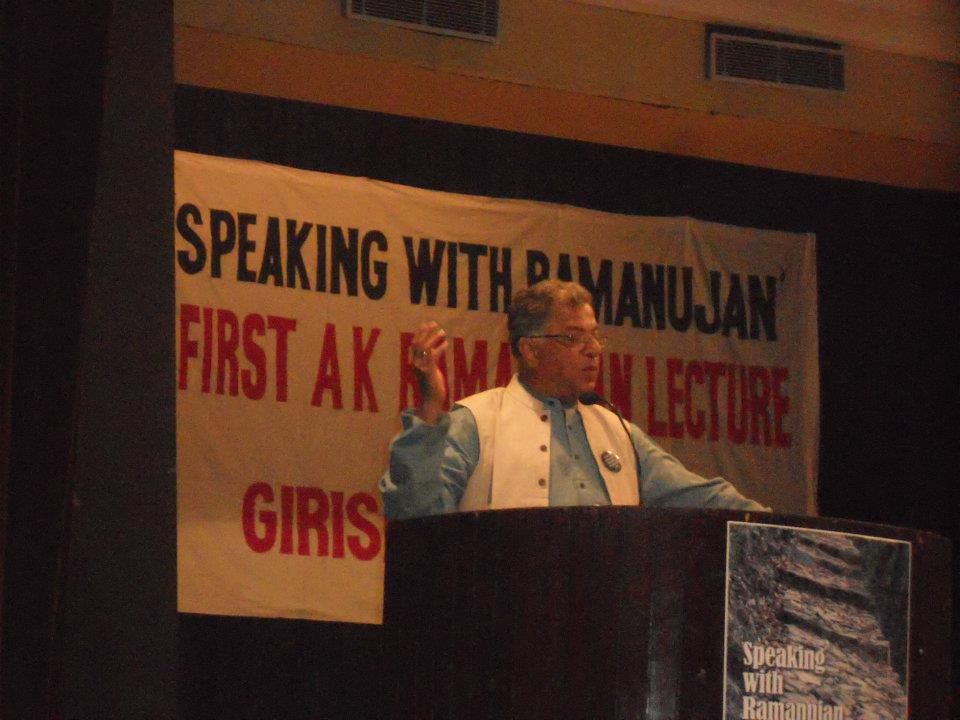

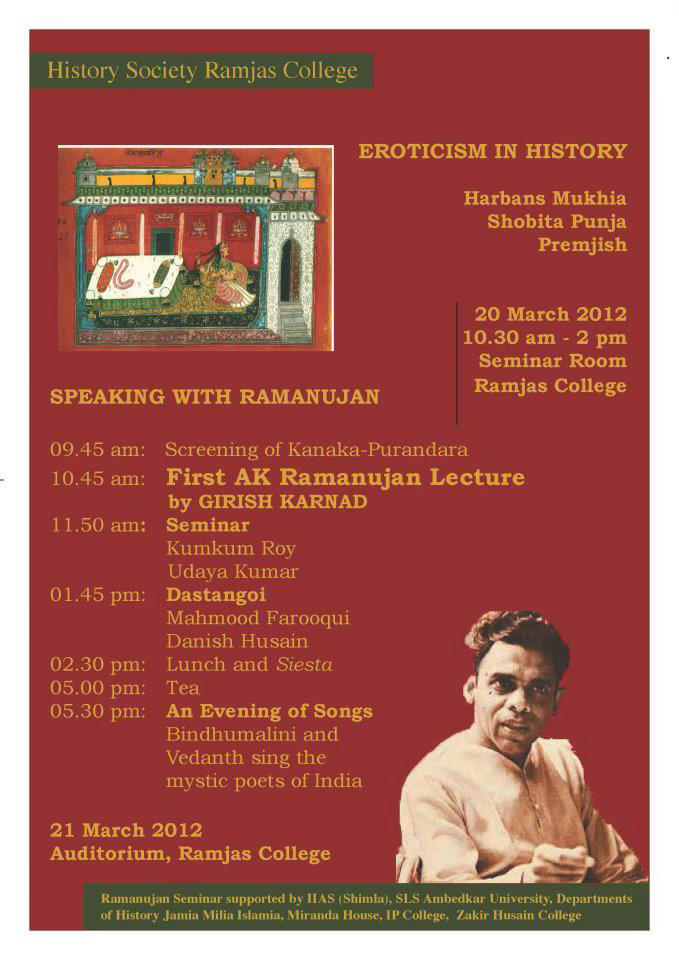

Not long after, Karnad delivered the first AK Ramanujan Memorial Lecture at Delhi University. The hall at Ramjas College was packed. Students, scholars and civil society gathered to reaffirm their regard for the beloved connoisseur and authority on India’s “indissolubly plural” literary heritage.

The lecture was not political; Ramanujan deserved more than a polemic. But it was a quiet rebuke to the parties, and the intellectual tendency that Ramanujan himself had identified, which had now come to censor and malign him long after his death.

Near the end of the lecture, Karnad counted the ways that his friend’s work had shaped his own. He described the many hats Ramanujan had worn — poet, translator, folklorist, linguist — and counted the ways that his friend’s work had shaped his own. He concluded:

“You know, I am sure, of the akshayapatra – it refers to a pot which never gets empty, however generously you help yourself to its contents. Raman was an akshayapatra to me.”

Post Script:

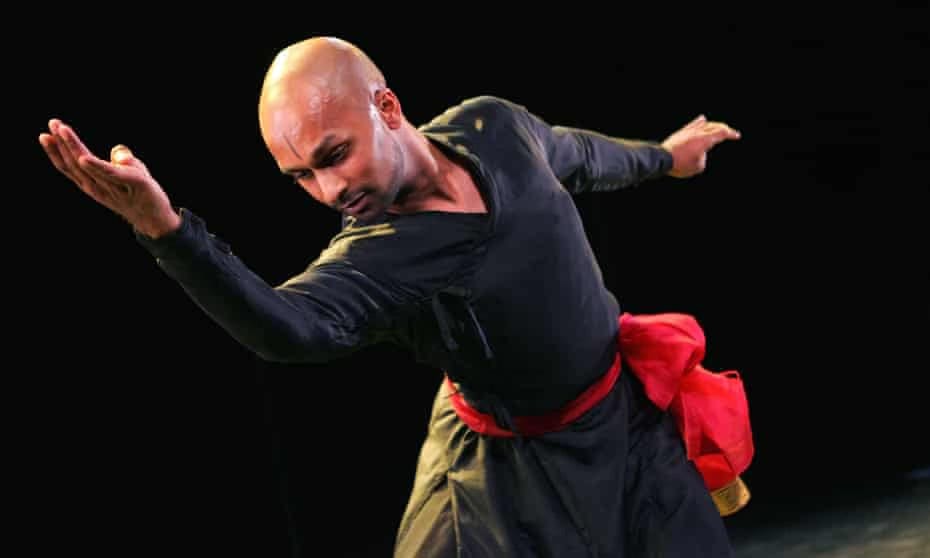

Between 2000 and 2003, Karnad lived in London and served as the director of the Nehru Centre, the cultural wing of the Indian High Commission. When the kathak dance prodigy Akram Khan asked him to read something alongside a performance – “poetry that evoked a sense of the ancient past and yet gelled with his almost propeller-like dance movements” – Karnad chose a dozen short Sangam-era poems from Ramanujan’s Poems of Love and War (1985).

“Even on stage, I could feel the electricity generated by Akram Khan’s whirling to the ancient poems. If I have ever felt close to bliss, this moment was it.”

This newsletter and the Instagram and Facebook pages it is tied to are part of an open archive of Girish Karnad’s life and work conceived by Raghu and Chaitanya as a way to keep his wide legacy alive and in public view. Its curator is Harismita.

A delightful & interesting read. So much one did not know. Looking forward to the next newsletter.