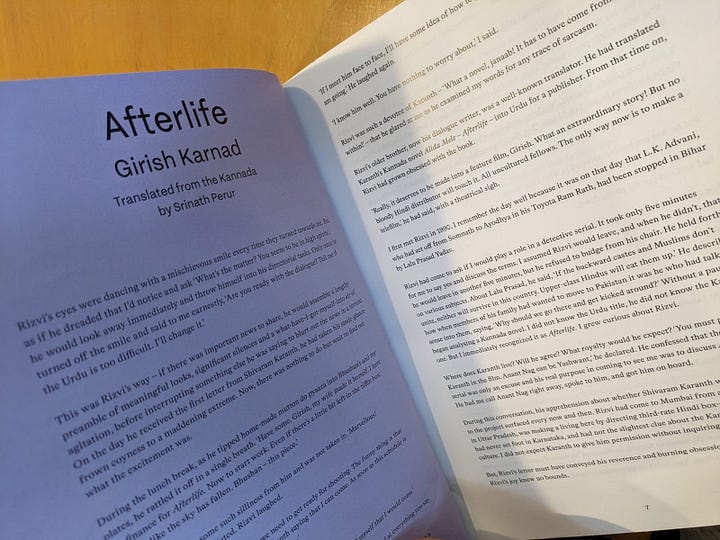

We're happy to present a special edition of the newsletter, sharing ‘Afterlife’, Srinath Perur’s recent translation of Girish Karnad’s short story ‘Alida Mele’.

Published in the 1998 Deepavali issue of the Kannada Prabha, the story shares its title with a famed Kannada novel by K. Shivarama Karanth. Karnad's story is a piece of auto-fiction where Girish Karnad himself is a character in conversation with Rizvi, a man who enthusiastically wishes to adapt Karanth’s novel into a film. The short story was also included in Aagomme Eegomme, a collection of Karnad’s assorted writings and speeches in Kannada.

Rizvi’s eyes were dancing with a mischievous smile every time they turned towards me. But, as if he dreaded that I’d notice and ask, ‘What’s the matter? You seem to be in high spirits,’ he would look away immediately and throw himself into his directorial tasks. Only once, he turned off the smile and said to me earnestly, ‘Are you ready with the dialogue? Tell me if the Urdu is too difficult. I’ll change it.’

This was Rizvi’s way — if there was important news to share, he would assemble a lengthy preamble of meaningful looks, significant silences and a what-have-I-got-myself-into air of agitation, before interrupting something else he was saying to blurt out the news in a torrent. On the day he received the first letter from Shivaram Karanth, he had taken his smile-glance-frown coyness to a maddening extreme. Now, there was nothing to do but wait to find out what the excitement was.

During the lunch break, as he tipped home-made mutton do pyaaza into Bhushan’s and my plates, he rattled it off in a single breath. ‘Have some, Girish, my wife made it herself. I have got finance for Afterlife. Now to start work. Even if there’s a little bit left in the tiffin box, she acts like the sky has fallen. Bhushan — this piece.’

I was anticipating some such silliness from him and was not taken in. ‘Marvellous! Congratulations!’ I shouted. Rizvi laughed.

‘K.P. Productions has agreed. So we need to get ready for shooting. The funny thing is that I have just received a letter from Karanth saying that I can come. As soon as this schedule is finished I’ll go to Sha — Where’s that? — Sha —’

‘Saligrama.’

‘Haan. Yes. I’ll go to Shaligrama. Karanth didn’t ask me, I said myself that I would come.’

‘Rizvi-ji, Karanth is not easily satisfied. Don’t think that he’ll simply nod at everything you say. He might even want to write the script himself.’

‘Why do you say that? I have received three letters from him already. He’s not laid down a single condition in any of them,’ he said, with the air of a person who has won an argument. ‘If I meet him face to face, I’ll have some idea of how to portray him in the film. That’s why I am going.’ He laughed again.

‘I know him well. You have nothing to worry about,’ I said.

Rizvi was such a devotee of Karanth — ‘What a novel, janab! It has to have come from within!’ — that he glared at me as he examined my words for any trace of sarcasm.

Rizvi’s older brother, now his dialogue writer, was a well-known translator. He had translated Karanth’s Kannada novel Alida Mele — Afterlife — into Urdu for a publisher. From that time on, Rizvi had grown obsessed with the book.

‘Really, it deserves to be made into a feature film, Girish. What an extraordinary story! But no bloody Hindi distributor will touch it. All uncultured fellows. The only way now is to make a telefilm,’ he had said, with a theatrical sigh.

I first met Rizvi in 1990. I remember the day well because it was on that day that L.K. Advani, who had set off from Somnath to Ayodhya in his Toyota Ram Rath, had been stopped in Bihar by Lalu Prasad Yadav.

Rizvi had come to ask if I would play a role in a detective serial. It took only five minutes for me to say yes and discuss the terms. I assumed Rizvi would leave, and when he didn’t, that he would leave in another five minutes, but he refused to budge from his chair. He held forth on various subjects. About Lalu Prasad, he said, ‘If the backward castes and Muslims don’t unite, neither will survive in this country. The Hindu elites will eat them up.’ He described how, when members of his family had wanted to move to Pakistan, it was he who had talked sense into them, saying, ‘Why should we go there and get kicked around?’ Without a pause, he began analysing a Kannada novel. I did not know the Urdu title, he did not know the Kannada. But I immediately recognised it as Afterlife. I grew curious about Rizvi.

Where does Karanth live? Will he agree? What royalty would he expect? ‘You must play Karanth in the film. Anant Nag can be Yashwant,’ he declared. He confessed that the detective serial was only an excuse and his real purpose in coming to see me was to discuss Afterlife. He had me call Anant Nag right away, spoke to him, and got him on board.

During this conversation, his apprehension about whether Shivaram Karanth would assent to the project surfaced every now and then. Rizvi had come to Mumbai from a remote village in Uttar Pradesh, was making a living here by directing third-rate Hindi box-office films, had never set foot in Karnataka, and had not the slightest clue about the Kannada language or its culture. I did not expect Karanth to give him permission without meeting or discussion.

But, Rizvi’s letter must have conveyed his reverence and burning obsession. Karanth agreed. Rizvi’s joy knew no bounds.

One day he said, ‘Why don’t you take this novel and make a Kannada art film? If you say yes, I will secure the finances somehow.’

As if in reply to his question, I said, ‘My friend B.V. Karanth has done Chomana Dudi.’

‘Oh! I’ve seen it.’

Rizvi had watched every single art film made in Kannada. He critiqued them, too. But his real interest lay not in the films themselves or their artistry. He watched them to find what might prove useful while making Afterlife. The day he watched Ghatashraddha, he had rung me in an exuberant mood.

‘Look here, Girish. You said, “Brahmin widows used to have shaven heads, and so should the two widows in our film.” I said, “No, that’s impossible. Our Hindi audience will never accept it.” To which you said, “Authenticity” — “Authenticity,” you said. The young widow in Ghatashraddha doesn’t have a shaven head. Now what do you have to say?’

But he was not really interested in what I had to say.

‘Tell me, which senior Hindi heroine will shave off her hair for a role? You’re too much!’ he had said and put the phone down.

The question of how the Brahmin widows were to be portrayed was not merely about what was acceptable to the stars. It was the beating heart of Rizvi’s telefilm. Because as soon as Rizvi reached the middle of the book, he, like a man mired in quicksand, stopped moving ahead and went deeper and deeper.

‘What an extraordinary scene! Karanth’s going to that village. Meeting his friend Yashwant’s adoptive mother there. Restoring the temple to fulfil the old woman’s longing. And, as a result, the coming together of those two old women who had lived as enemies in the same village. Wah! Wah! Lajawab!’

Rizvi’s voice would quiver with emotion. I had heard the same thing a half-dozen times and was sick of it. I said, ‘That’s all fine, Rizvi-ji, but you’re only narrating the first half of the novel. It has many more characters. There’s more to the plot. Karanth goes on to meet Yashwant’s wife, his children. You never mention these parts.’

Rizvi glanced in my direction, shook his head and called out, ‘Abdul...’. He whispered something in the ear of the production manager who materialized from nowhere. He acted as if he had forgotten that Bhushan and I were present. Then he turned to Bhushan,

‘Do you know the story? A man named Yashwant lives a solitary life and dies alone in a place where he knows no one. He has asked Karanth to dispose of his assets. Karanth was not a close friend or anything, only an acquaintance. Still, he sets out to find Yashwant’s family members. When he comes to the village, Yashwant’s adoptive mother, Parvatamma —’

Rizvi was again racing towards the quicksand. He saw that I was about to stop him, took a script from his bag, and laid it out in front of Bhushan.

‘Look at the graph. Yashwant is dead at the beginning. Alone. No relatives near him. But with Karanth’s efforts, and for the solace of that widow, a temple is brought back to life. The other characters, fine, we can adjust them somewhere. But the crux of the film is this, Bhushan — the resurrection of the temple! It is a sign of man’s spiritual awakening.’

Then, he turned to me.

‘The last scene of our film. Imagine this. The ruined temple is being rebuilt. The two old women are embracing each other and weeping. You — that is, Karanth — turn to look back as you are leaving the village. Your friend Yashwant was an atheist. You are also an atheist. But your life’s fulfilment lay in reviving that temple! Tears in your eyes. The joy of having fulfilled your late friend’s dearest wish! What do you think, Bhushan-ji? How is the climax?’

‘If you really want my opinion, I’ll tell you,’ said Bhushan, and then he proceeded to say what any actor would say. ‘It’s fine if as usual, you don’t pay me this time, also. But the most suitable actor to play Yashwant is me.’

Rizvi laughed loudly. As if this were a signal, an assistant director came up and said, ‘Lighting ready.’ Rizvi slipped the script of Afterlife into his bag, said, ‘The first shot is yours, Bhushan-ji’, began speaking to the assistant director in the same breath and went away.

‘He talks too much,’ Bhushan complained. ‘There’s only one reason I act in his films: his wife’s home-made meat curries.’

I went to the make-up room.

*

Some two weeks later, Rizvi died.

I was in Singapore for a shooting. The film’s producer had said, ‘The shooting should have happened in Kashmir. But there you have these Kashmiri terrorists. Because of them all this “Go to Switzerland, go to Singapore” business. This country needs a government that will teach them a proper lesson.’ He spoke as if the extremists were lurking in wait just to sabotage his film. Then he said, ‘Our actors want the same thing. Switzerland! Singapore! Who cares about the industry?’ He grumbled that if not for the fuss with these stars, the Kashmiris could all have been thrashed, and he took us to Singapore.

When I returned, the Ayodhya turmoil had spread everywhere. I phoned Anant Nag, who usually knew what was happening behind the scenes in the political world. But he told me something else altogether.

‘Rizvi came to Bengaluru and met me. He paid me an advance. Talked non-stop. The very same evening, he left by bus for Udupi to meet Shivaram Karanth. There was an accident somewhere near Mulki. Apparently some luggage fell on his head. He was the only person on that bus to die. They say the body remained there for three days.’

That evening, I went to Rizvi’s place. It was an old house in a bylane between Bandra and Pali Hill. Rizvi had taken the place on rent when he first came to Mumbai around 1960. The property’s value had soared. The landlord had been after Rizvi to vacate the house, even offering him a spacious flat for free if he obliged, but Rizvi had been pushing away his appeals.

‘Only a house can be a house, not a flat,’ he argued.

Rizvi’s wife sat in the corner of a sofa in the hall. She did not speak. Her tears flowed freely but she did not sob.

The daughter must have been out somewhere.

Rizvi’s son, Yakub Hasan, was twenty or twenty two. He brought me some water and told me what had happened.

After Rizvi died in the accident, the Mulki police had got his address from his wallet and contacted the Mumbai police. When they informed the family, Rizvi’s older brother — the translator of Afterlife — left for Udupi. By then, the Muslims of Mulki had come forward saying, ‘It seems a Muslim has died. If you hand over the body to us we will perform the burial.’ But the police could do nothing until the brother arrived. The body lay unclaimed and rotting for three days, apparently. The brother who had gone all the way to Mulki also returned without meeting Karanth.

Yakub spoke evenly. There was none of the rush of his father’s speech, no words tripping over each other. He looked like his mother. Round face. Wide mouth. Not short, like Rizvi.

‘Uncle, I need some help from you,’ he said. ‘K.P. Productions has agreed to finance the film. My father had taken an advance of one lakh rupees. He has already used the money to pay people. Now, we have to somehow finish the film.’

I felt Rizvi would not have explained the matter so clearly, concisely, slowly. His son had not inherited his wry smile, his sarcasm. For some reason, I felt desolate.

‘What is the budget in the agreement?’ I asked.

‘I’ll show you,’ Yakub said and went inside.

Rizvi’s wife suddenly began to speak.

‘Our daughter is now grown up. I was after him to get her married. But he said the film of the Kannada story would cover the wedding expenses, so he would finish it first. What has he got after working in this industry for thirty years? He met household expenses somehow but he didn’t save enough for his daughter’s wedding. He would say, “Let this one film get made, we can then save as much as we want.”’ After a pause, she said, ‘Hearing such words again and again killed any dreams I had. Now he is gone too.’

‘Bhabhi-ji, I will do everything I can,’ I said.

Yakub came back with the file. I was shocked to see the terms. Rizvi had agreed to deliver a two-hour telefilm on 16 mm film for only eleven lakhs.

There must be a mistake somewhere, I thought, repeatedly flipping through the pages. Maybe there was something additional hidden in there. As if this were not bad enough, he had promised two songs in the film.

‘Yakub, let’s go and talk with K.P. Productions,’ I said.

‘I’ll give you their number. Should I come too? I don’t understand anything about all this. My father never let me go anywhere near a shooting,’ he said.

‘Time for you to learn,’ I told him.

Rizvi’s wife looked up and glanced at her son.

‘You have no objection, I hope?’ I asked her.

‘Rukhsana has to be married. Let him do it this once,’ she said.

‘Uncle, we have to inform the author of the novel.’

‘Leave that to me,’ I said.

I phoned Shivaram Karanth that very day. He said, ‘I have already given my permission. Now anyone can direct it on behalf of the Rizvi family.’

Then, I made an appointment with K.P. Productions.

Life had come to resemble art. Like Yashwant, Rizvi too had died alone, far from his friends and relatives. And I had begun to take on Shivaram Karanth’s role in reality.

*

Plastic trophies plated with gold and silver commemorated runs of twenty five, fifty and seventy five weeks. In the middle of posters with of-dressed heroes and heroines, against a saffron backdrop, there was a large OM pierced by a trishul. Below it, the line: garv se kaho hum Hindu hain. Say it with pride—we are Hindus.

I don’t know if Yakub noticed all this.

‘No question of increasing the budget. It’s impossible,’ said Kailash Prasad of K.P. Productions, underlining his helplessness by spreading his arms wide. ‘Why did Rizvi agree if it is not possible to make the film in 11 lakhs, ?’

Yakub looked at me, helplessly.

‘I don’t know,’ I said. But I had begun to know.

The producer was a shrewd man who knew his way around money. The facts of the matter were becoming clear to me as we spoke. Because Rizvi had to make Afterlife at any cost, he had agreed to an impossibly low budget. He had put off his daughter’s wedding for the sake of his obsession. He had lied to his wife that the film would pay for the wedding. Kailash Prasad had seen Rizvi’s passion and realized that he would accept any budget. Had Rizvi continued with this project, he would have had to take a loan of three to four lakhs. A personal loan. His daughter’s wedding would have been further delayed. There would have been more complications.

I got up. ‘The film cannot be made in eleven. Sorry. We’ll leave now. Come, Yakub,’ I said.

‘What about the advance?’

‘Rizvi didn’t keep it for himself. He distributed it to people involved with the film. Including me. Now, it can only be used towards making the film. Otherwise it’s gone. Think it over and let us know. I will make the film myself, if you can go up to eighteen.’

I could have said sixteen. But I added two lakhs for wedding expenses. I knew that the haggling wasn’t over.

Yakub was troubled. He was concerned that we were doing Kailash Prasad an injustice. I handed him the script and the budget and said, ‘If that rogue agrees, it’s fine. If not, make other arrangements for your sister’s wedding. Don’t fall into the trap of trying to finish the film in eleven lakhs.’

I took a taxi and went home.

I knew that Rizvi was not a fool. That said, what can you call someone who gets into an absurd commitment like this? Naive? Mad? Perhaps there isn’t a word for it in Kannada. But, there is one in Arabic. Majnu! Rizvi was a majnu, crazy about the first sixty pages of a novel.

*

6th December. The Babri Masjid was demolished.

Bhushan phoned the next day. ‘Good riddance. This is how they should be taught a lesson. Otherwise they don’t learn,’ he said.

My friends and family were all nodding in approval. The world around me had grown aroused by its own violence and ejaculated.

About a week later, Yakub Rizvi called as I was drinking my morning tea.

‘Uncle, are you going to be at home for another half hour?’

‘Yes. I have an afternoon shooting shift...’

‘I am coming. I’ll be there in half an hour.’

‘What happened? Tell me over the phone.’

He had already put the phone down.

The door bell rang after twenty minutes. I opened the door and for an instant, I thought it was Rizvi. Even as I said, ‘Come, come, sit down’, a question had begun to trouble me. The last time I saw him, there had been no resemblance between Yakub and his father. Why was I now reminded of Rizvi?

‘What’s the news?’ I asked.

‘Wait, uncle. Have these sweets first. Then, I’ll tell you the news!’ he said and brought out a box of sweets from his bag. He looked at me, smiling. I recognised that mischievous smile at once. Ignoring the question asked and saying something else – that, too, was Rizvi’s trademark.

‘Why the sweets?’

‘My mother has sent them for you. It’s a special Hyderabadi recipe. Shahi tukda. She insists that you try one before we talk.’

As I savoured the shahi tukda I asked, ‘Has your sister’s marriage been fixed?’

‘No. But it is fixed that it will be fixed.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Uncle, K.P. Productions has agreed to put 17 lakhs into Afterlife. They called last evening.’ The words came tumbling out, one over the other.

I did not say anything.

‘They said we should start as soon as possible.’

‘Yakub, it’s not possible any more to make Afterlife.’

Like father like son, he rushed ahead without considering what I had said.

‘If you tell me what your total commitment is...’

‘Yakub, sorry. I don’t want to make the telefilm.’

The words reached him this time. He was bewildered. He had been standing until now. Stunned, he sat down in a chair. As if laughing would solve all problems, he looked at me and let out a half laugh.

‘Why, uncle? You yourself offered to do this. They are saying seventeen. But if it must be eighteen...’

His voice had weakened. He sounded like his mother, who had grown tired of standing at the threshold of prosperity, hearing story after story about the future.

How could I explain it to him? I tried.

‘Look, your father was so taken by that story for one reason only. For the temple that is restored at the end of the film. For him, it was a symbol of humanity. But now... phrases like ‘temple construction’ and ‘temple restoration’ mean something else altogether. They have become poisonous.’

‘Meaning?’

I could not tell if Yakub was trying to understand or if he was lost in his own thoughts.

‘The goons who brought down the Babri Masjid now want to build a temple there. Don’t you know that?’

‘Who doesn’t know that, Uncle?’ Yakub said, laughing. ‘But how is it connected to you?’

I got up, went to the window and looked outside. Immediately, I felt I should not have done this. In every television serial, older people go and look out of the window when they want to belt a speech.

‘It is connected to everything. The savagery in Ayodhya has corrupted the very idea of temple building. There is an abandoned corpse lying on the ruined foundation of the Babri Masjid — that of Hindu culture,’ I began. I didn’t know how to go further without becoming melodramatic. So, I cut short my remarks. ‘It is not possible for me, at least, to do this film,’ I said.

Yakub sat there, looking at me.

I felt I was talking like Rizvi, circling the mountain without coming to the point. Something like the demolition of the Babri Masjid is never an isolated incident. It infects every part of our culture like a plague. Even a Kannada literary work, thirty-two years after it was written.

‘Uncle,’ Yakub began. He stopped and went on, ‘I didn’t want to say this, but I will. If this film is made, my sister will get married. You agreed to direct this film, and for that... I should not say it... it’s difficult to express just how grateful our family is.’

He paused for a moment. ‘You are our only hope,’ he said.

How was I to explain to him? When the film is broadcast on television tomorrow, who will tell the viewers the backstory of Rizvi’s daughter’s marriage? All they will see is me, exploiting a great Kannada novel to boast about a shameful incident.

‘It is not only the Babri Masjid that is no more, Yakub. Your father’s dream has died with it too,’ I should have said. But I stood without speaking, looking out of the window.

There was a long silence.

‘Your wish,’ Yakub said as he got up. ‘It will be wrong of me to insist when you don’t want to do it.’

How many times could I repeat what I had already said? Or not said?

‘All right, I’ll take your leave,’ he said and went towards the door.

The box of sweets was on the table. The script for the telefilm Afterlife lay right next to it. ‘Yakub, take that with you,’ I said, pointing to the table.

‘My mother sent it especially for you,’ he said.

Flustered, I said, ‘Not the sweets, the script.’

Yakub looked at me. For an instant, I thought I saw a smile flash in his eyes.

‘No, uncle. What use is it to us now? I’ll take your leave,’ he said. And went away.

* * *

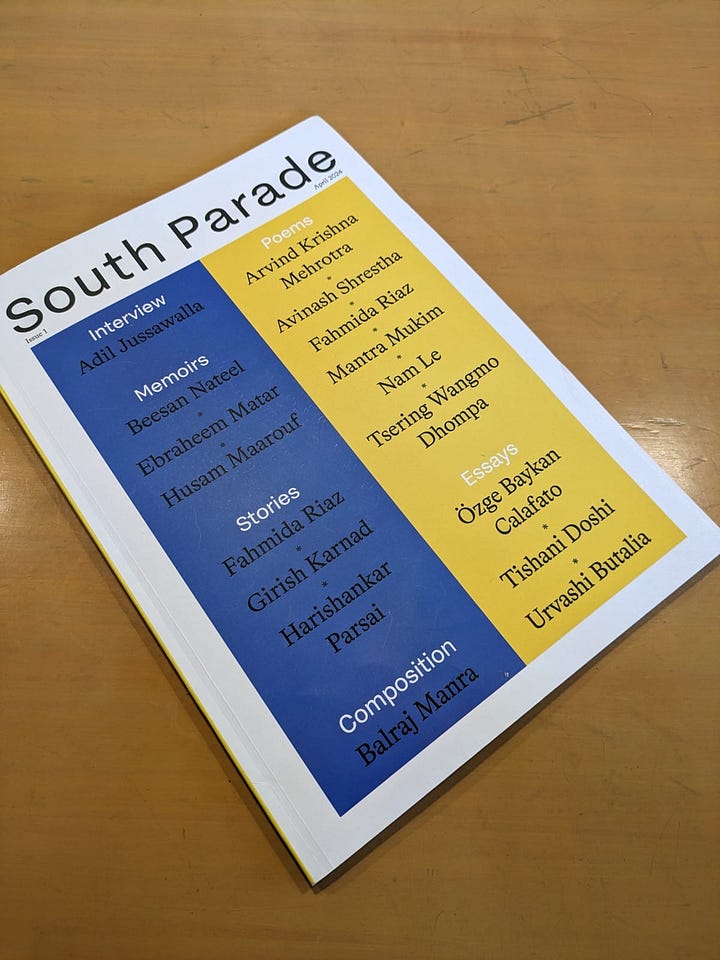

Srinath Perur’s translation of Karnad’s short story, ‘Afterlife’, is open to public readership here for the first time since its appearance in the inaugural issue of the new Bengaluru-based literary journal, South Parade (April 2024).

This newsletter and the Instagram and Facebook pages it is tied to are part of an open archive of Girish Karnad’s life and work conceived by Raghu and Chaitanya as a way to keep his wide legacy alive and in public view. Its curator is Harismita.