#2: The Mahabharata

Welcome to ‘Tell It Again’, a newsletter that dives into the life and work of Girish Karnad. We picked out the title from a line in Nagamandala:

“You can't just listen to the story and leave it at that. You must tell it again to someone else.”

We hope to tell his story again, through glimpses into his work, his papers, his circle of friends and collaborators, and their great creative milieu.

Each week, we share eclectic material around a new theme. This week: Girish Karnad and the Mahabharata.

“The only book he had ever insisted that we read — putting copies in our hands — was the Mahabharata.”

Raghu and Radha Karnad, Afterword, This Life At Play.

In 1959, when Girish Karnad was about to leave for Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, he felt compelled to read the epics and the Puranas before his departure. He had grown up watching these stories performed by lamplight, by Yakshagana and Company Natak troupes. Now he reached for C. Rajagopalachari’s concise but complete versions of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. This is the decision that would eventually lead him to write his first play, Yayati.

Every aspect of this play took him by surprise, as Aparna Dharwadker notes:

“That it was a play and not a cluster of angst-ridden poems, that it was written in Kannada instead of English, and that it used an episode from the Mahabharata as its narrative basis.”

This choice “nailed me to my past,” Karnad said. It set him on a path of drawing narratives from myth, history and folklore, which dominated his playwriting for the next four decades.

In the myth of Yayati, a king is cursed with decrepit old age, and Puru, his youngest son, agrees to bear the curse on his behalf. In This Life At Play, Karnad recalls:

“I was excited by the story of Yayati, where a son exchanges his youth with his father’s old age. The situation was both dramatic and tragic. But the question that bothered me even as I was finishing the story was: If the son had been married, what would the wife do? Would she have accepted this unnatural arrangement?”

This imaginary character’s response became the seed of his first play, written at the age of 22:

“This was the first scene that formed in front of my eyes: the confrontation between Yayati and Chitralekha. ... As I thought about it, the rest of the play began to take shape around this climax. I did not feel as if I was writing a play… It was as if a spirit had entered me.”

At the time, Karnad was a young man facing his own burdensome questions: Would he return to India when he was done at Oxford? What were his responsibilities, as a young man, to his own father, his family, or his country?

When Karnad wrote the play, he could relate to the son, Puru, and the weight of obligation he feels in the story. When he read the play again, much later in his own life, he found himself identifying with the desperation of the father.

Watch: The Structure of the Play, a lecture by Karnad on Yayati at the Sahitya Rangabhoomi Pratishthan in 2015.

A second story from the Mahabharata also made an impression on Karnad at that early point. This one, though, would take 37 years to become a play: Agni Mattu Malé, or The Fire and the Rain.

Anmol Tikoo, who co-hosted the interview podcast, The River Has No Fear Of Memories, tells us:

Girish Karnad’s mythic plays are bookended by the Mahabharata — Yayati at one end, and the Fire and the Rain at the other. In the podcast, he told us how most of his plays (Yayati being the exception) didn't just come to him, how he chose to meticulously enrich his traditions. Like modernist writers before him, he looked to the epics for inspiration, and arguably the Mahabharata was one of his “akshaya patras.”

The myth of Yavakri(ta) would sit with Karnad until 1993, when The Fire and the Rain was commissioned by the Guthrie Theatre, which had just staged the first professional US performance of Nagamandala. He wrote it in Kannada, and translated it into English right afterward.

“The split between nature and culture, body and mind appears in such earlier plays as Hayavadana and Bali, but in Agni Mattu Male the duality is expressed for the first time as the explicit opposition between brahmin and shudra,” Aparna Dharwadker observes.

Here’s Anmol Tikoo again:

In the Fire and the Rain, he creates this intricate structure, including a play within the play, that allows us to look beyond the elites and their obsessions. This is the fire versus the rain — the Agni of the dominant castes and their scriptures, versus the Male of ordinary folks, their art and their concerns.

If Mahabharata is about the difficulty of being good, then Fire and the Rain gives a positive counter to that in the transgressive love of Arvasu and Nittilai. Caring for others, those who aren't akin to us, is what keeps the world going and that is what turns out to be the natural order of things.”

Listen to episode 8 of The River Has No Fear of Memories, where Karnad speaks to Tikoo and Arshia Sattar about the Mahabharata, history, and much more.

The Fire and the Rain evoked a rare “intensity of responses, both negative and positive,” Dharwadker writes, which are easily explained: “It is a dense, intellectually ambitious, autumnal play structured around ideas… and a plethora of tangled relationships which unfold with a rare economy and intensity of words and emotions.”

Two responses to the play, by Shanta Gokhale and Manu Chakravarthy, capture this breadth of critical responses.

Shanta Gokhale hailed it as a play that “cannot be reduced to an indoor performance. It should really be an annual ritual, enacted under the open sky by actors with resonant voices…”

Manu Chakravarthy, on the other hand, interrogated Karnad for even choosing the vehicle of Hindu myth. “If Karnad’s faith rests entirely on secular elements, why does he dig into the past as he very often does in his plays, drawing from mythological and historical sources?”

In a 1999 interview with The Sunday Herald, Karnad explained what drew him to mythological sources — the potential for exploring contemporary life through the material provided by Puranic legends.

“Pauranic plays have come to mean plays about Rama and Krishna, which involve bhakti. But there is so much else that is from the Puranas, there are such marvellous stories, which don't involve the gods at all. They don't involve Rama or Krishna. In the Vedas you find something, in the Upanishads you find them. [Agni Mattu Malé] is about a story from the Mahabharata, but which does not involve Rama, Krishna or any of the gods. It's a Vedic tale.”

As far as playwriting was concerned, he said:

“The story may be from the past. But the play must be about the present… I don’t deliberately try to make it a contemporary subject. If I have a contemporary consciousness, it will become modern because I am a modern writer writing about it, you see.”

Yet the Mahabharata was not just a store of minor legends from which to elicit modern literature. Karnad had an abiding, overarching interest in the central story of the Mahabharata war — and its potency in Indian history and society, even in the present day.

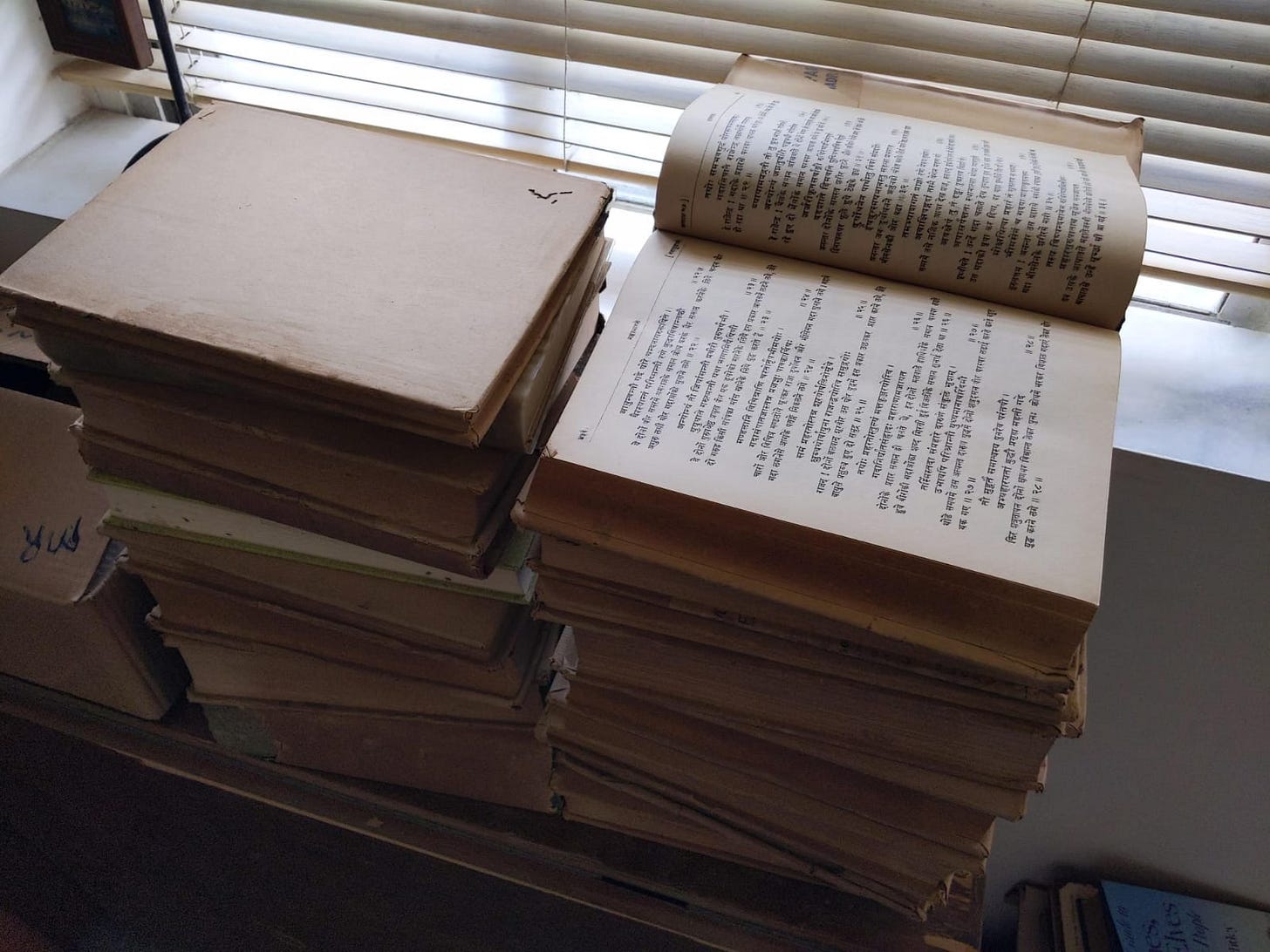

In his flat in Bombay, where he lived with his family through the 1980s, he kept a 14-volume edition of the Mahabharata in Sanskrit.

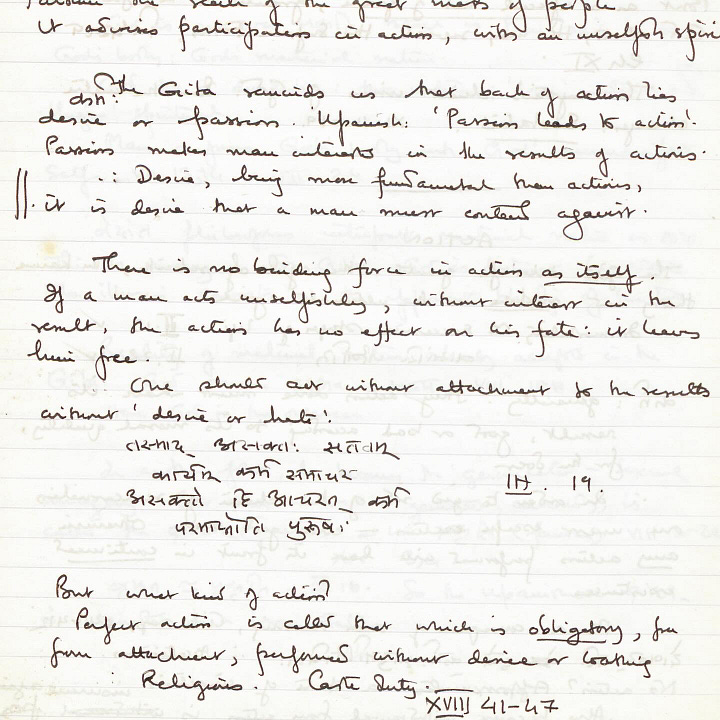

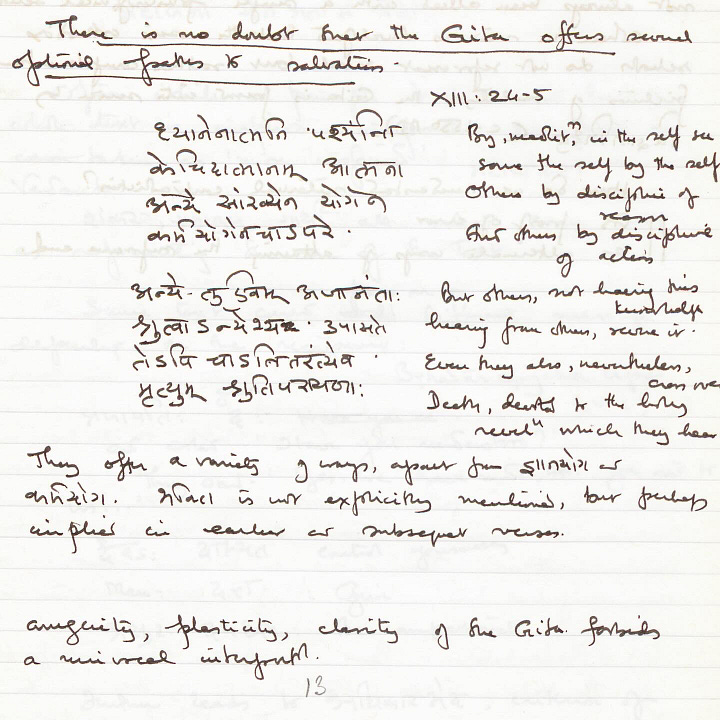

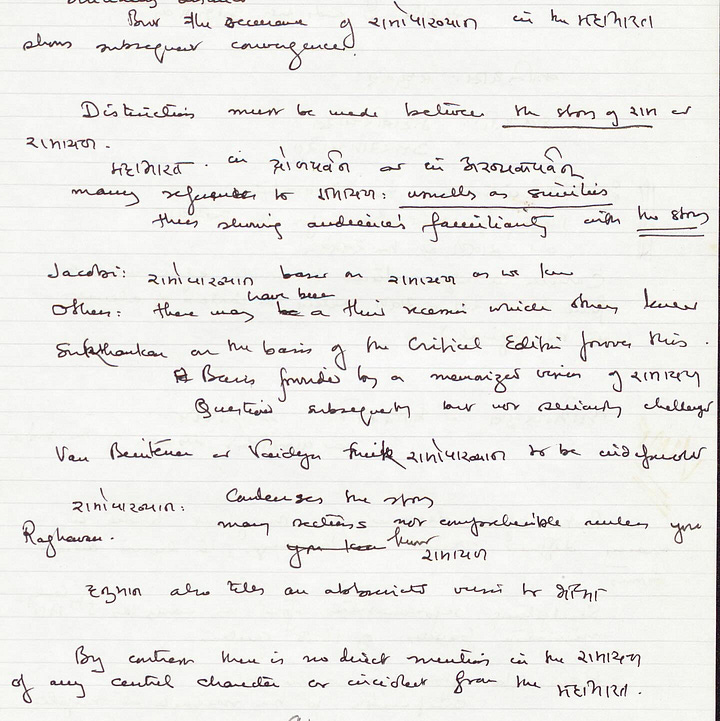

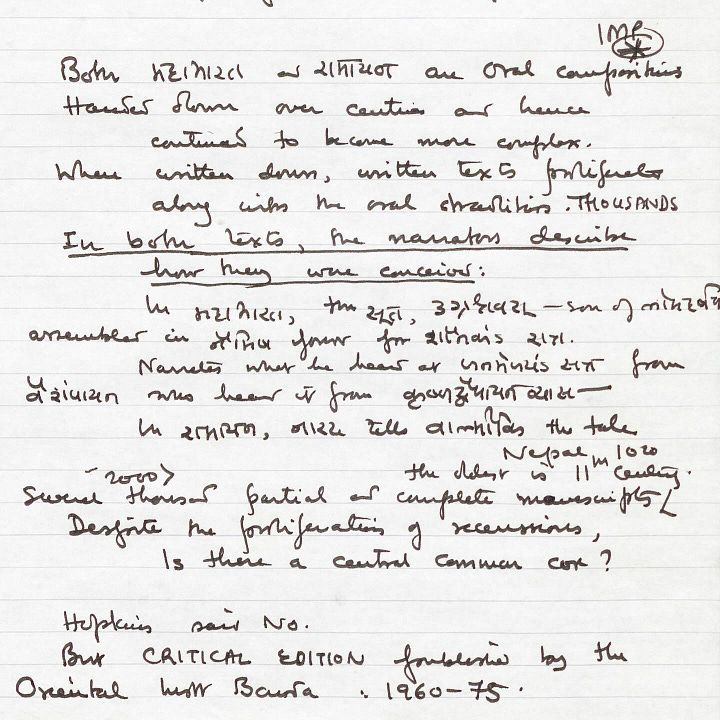

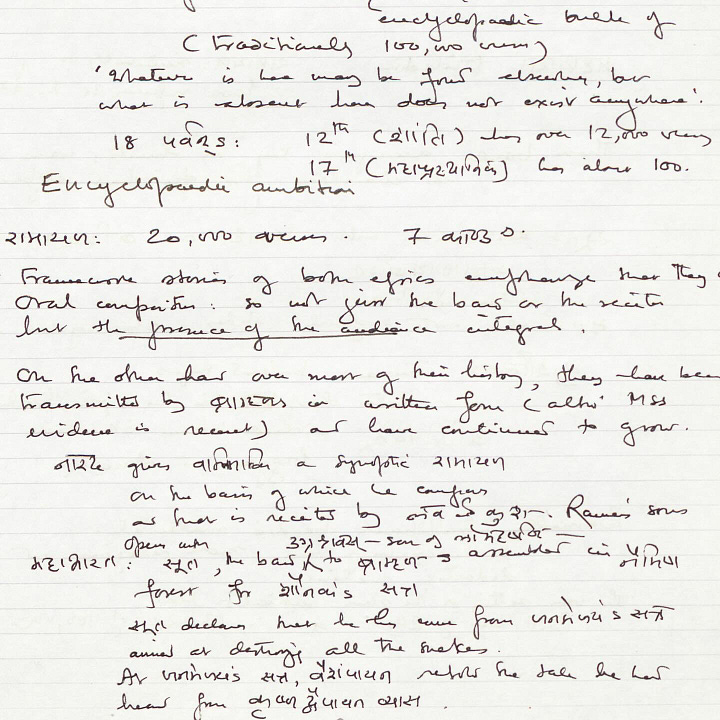

In the same period, he was a meticulous reader of academic writing about the epics (among other subjects). He filled notebooks with hand-written notes of his readings about the Mahabharata.

These notebooks, along with a diverse collection of his other papers and letters, are housed at the Ashoka Archives of Contemporary India.

His keen interest in the epic as a whole came in handy in 1997 when S4C, a Welsh TV channel asked Karnad to write a screenplay for an animated film of the Mahabharata. The producers, Chris Grace and Penelope Middelboe, had already created a collection of Welsh animation classics, adapting a number of British literary landmarks like The Canterbury Tales and the plays of William Shakespeare.

Middelboe wrote to us about working with Karnad:

“The way he welcomed our naïve attempts to understand the Mahabharata, without ever deliberately making us feel ignorant or misguided is the rare hallmark of a truly learned person. … He believed that we were sincere in our desire to animate this great classic and took that at face value.

I’m sorry we never made that screenplay into an animated film before the tide turned, sweeping away most funds for animation, unless inside Los Angeles.”

Karnad finished the screenplay — now also housed with his papers at the Ashoka Archives — but the film was never made. However, we can imagine what it might have looked like, based on S4C’s other work.

Then a few years later, while he was living in London as director of the Nehru Centre — the cultural institute of the Indian Embassy — Karnad was approached by the BBC to write and present an episode for the series “Art That Shook The World”. The subject: the Mahabharata.

KM Chaitanya shares a memory about Karnad’s response:

“Karnad told me: ‘I said to them that the Mahabharata was so vast in its expanse that they cannot put it alongside any other work of art in the world. I told them they might have to make a new series called ‘Art That Created The World’ if they wanted to make something on the Mahabharata. I suggested that instead of the entire Mahabharata, they could plan an episode on the Bhagavad Gita, which is an important part of the epic.’ ”

Andrea Miller, who produced the series, told us:

“I had decided the series should not be solely based on the Western canon. I’d been very influenced, years before, by seeing Peter Brook's stage production of The Mahabharata.

We had just been filming with Brook on another production which brought it all back to mind… Girish had fairly recently arrived in London and had been in the newspapers so we contacted him. I recognised his work as a movie star of course. I was thrilled when he said yes.”

The episode, directed by James Erskine, included interviews with Ramachandra Gandhi, Mark Tully and (against Karnad’s counsel, he later said) Murali Manohar Joshi, then a minister in the NDA-1 government. Watch a selection of clips from the episode here and here.

This newsletter only scratches the surface of Karnad’s life-long engagement with the epic – it can’t distil the substance of his views and insights. Those emerge in his plays and in the BBC Gita documentary. They are there in an intimate form, too, in his studious notes on the work of professional scholars. Even at the peak of his career, Karnad was still studying the epic. To him, after all, it was not just the story of an ancient or mythic war. “The Mahabharata,” he said, “is always our latest war.”

To end on a lighter note:

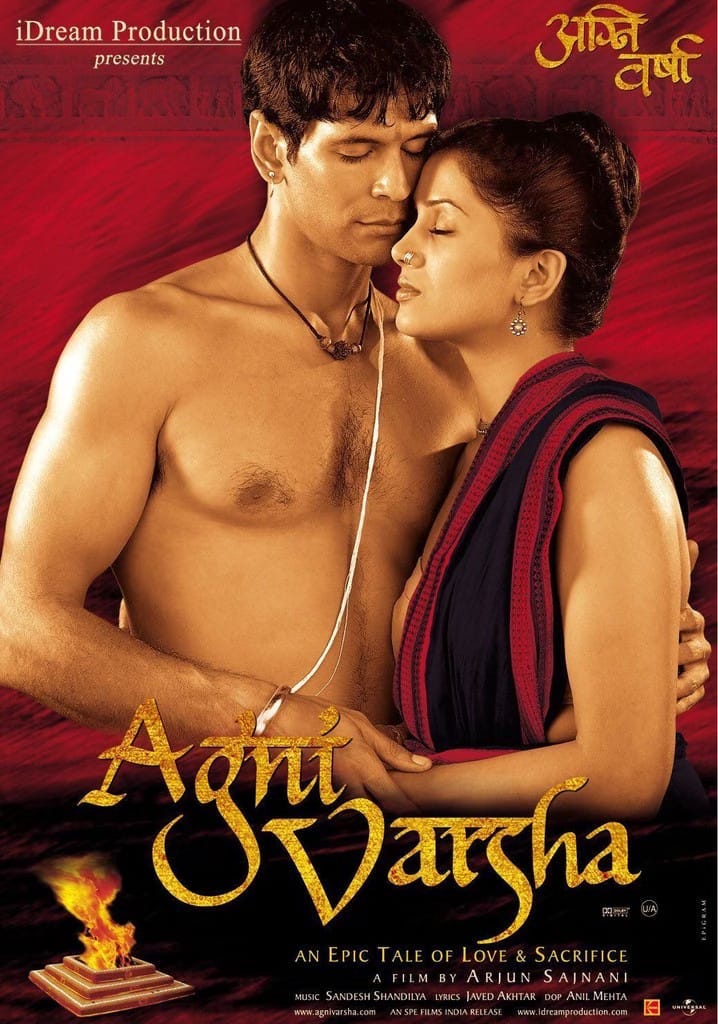

After the rousing reception given to Arjun Sajnani’s spectacular production of The Fire and the Rain in 1999 in Bangalore, he directed a film adaptation of the play in Hindi, Agni Varsha, released in 2002.

“The volcanic passions that rumble through ‘Agni Varsha: The Fire and the Rain,’ a dense, colorful dramatization of a portion of the Indian epic ‘Mahabharata,’ are literally earthshaking,” writes Stephen Holden in a 2002 film review in the New York Times:

“The relationship between heaven and earth throughout the movie is volatile, as the human characters, who imagine they have more power than they do, find themselves at the mercy of divine forces whose purpose remains enigmatic.”

For your viewing pleasure: Dole Re, a song from the film featuring Milind Soman and Sonali Kulkarni.

This newsletter, and the Instagram and Facebook pages it is tied to, are part of an open archive of Girish Karnad’s life and work conceived by Raghu and Chaitanya as a way to keep his wide legacy alive and in public view. Its curator is Harismita.

Join us on Instagram and Facebook – and share away if you enjoyed reading this!

We’ll see you in your inbox next week with a closer look at Girish Karnad on Ayodhya and the Babri Masjid.