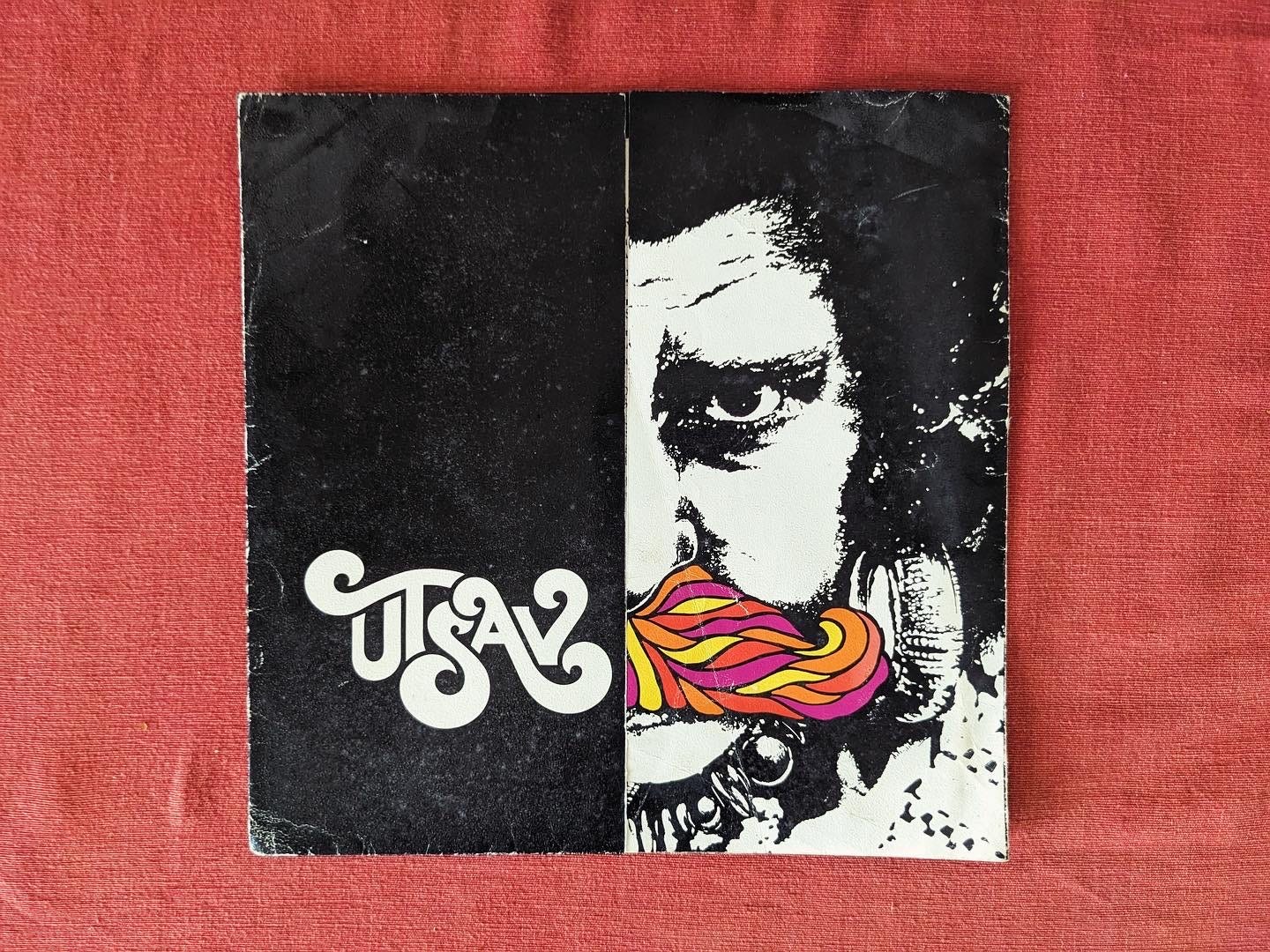

#1: Utsav

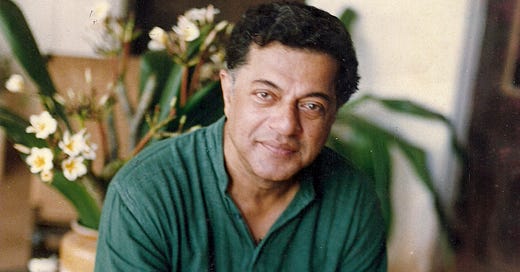

Welcome to ‘Tell It Again’, a newsletter that dives into the life and work of Girish Karnad. We picked the title out of a line from the opening of Nagamandala:

“You can't just listen to the story and leave it at that. You must tell it again to someone else.”

We hope to tell his story again, through glimpses into his work, his papers, his circle of friends and collaborators, and their great creative milieu.

This newsletter, and the Instagram and Facebook pages it is tied to, were an idea that Raghu and Chaitanya had held onto since 2019 – a way to keep Karnad’s wide legacy alive and in public view. Its curator is Harismita V.

Each week, we hope to share eclectic material around a new theme. Our first theme is Utsav.

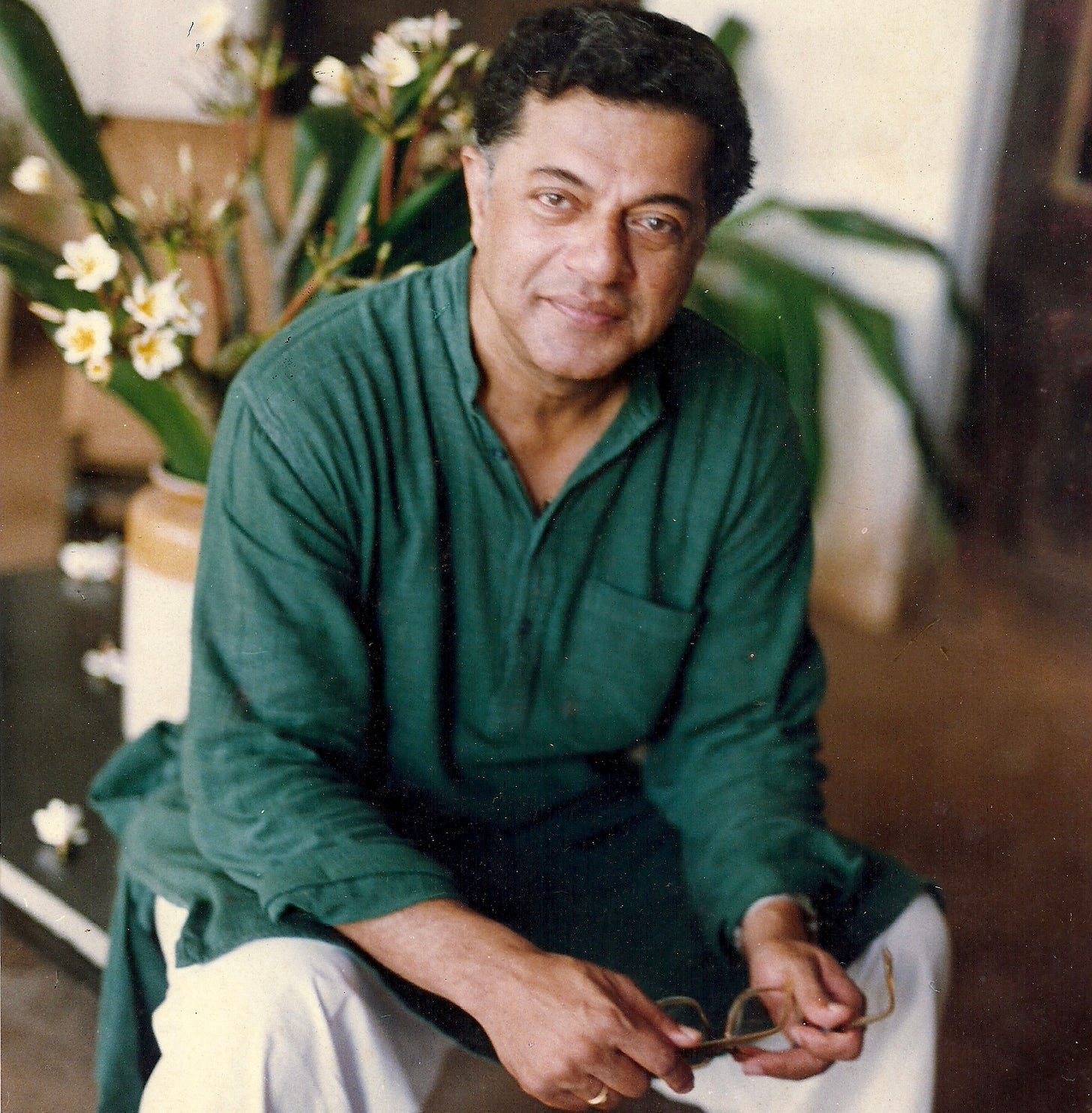

When Girish Karnad died in 2019, he was rewriting his Kannada memoir to publish in English. That process was never completed, but he did draft a chapter about making the epic, erotic and contentious 1984 film Utsav.

“The story of the making of Utsav is as tangled and as prone to swinging wildly between melodrama and comedy as the plot of the original Mricchakatika on which it is based. The project began like a folktale, with me pretending to be someone else in a foreign land, and grew, progressively, to engulf my whole life.”

The film was conceived as a spectacular cinematic production of a beloved Sanskrit drama. Its ingredients were to be:

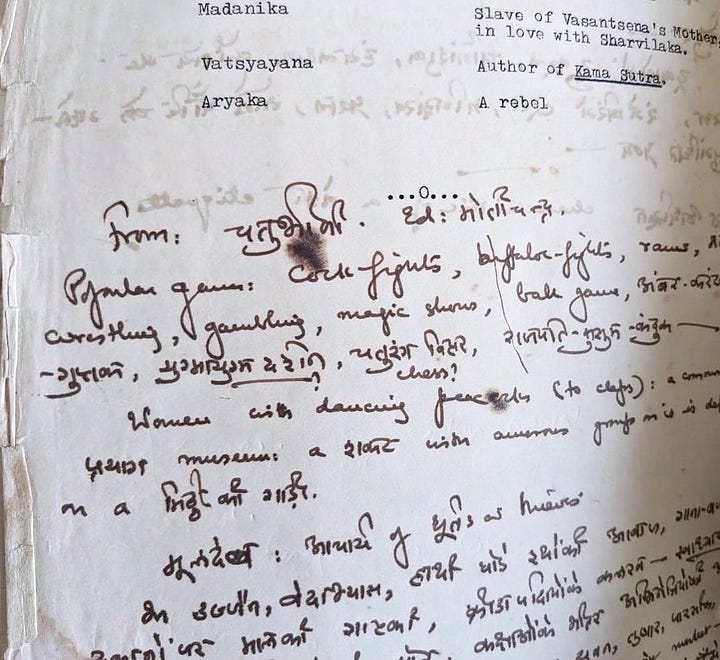

A screenplay based on Sudraka’s Mricchakatika, by Girish Karnad and Krishna Basrur.

An expansive cast of established stars and emerging actors from the Hindi film industry.

A soundtrack by Laxmikant-Pyarelal.

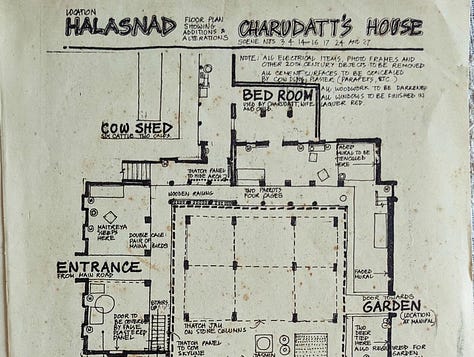

Art direction and cinematography by Jayoo and Nachiket Patwardhan and Ashok Mehta.

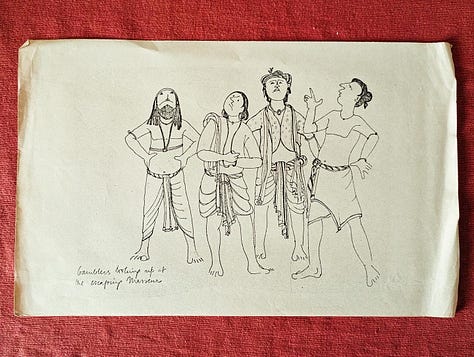

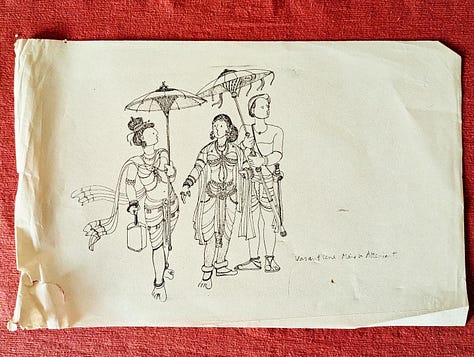

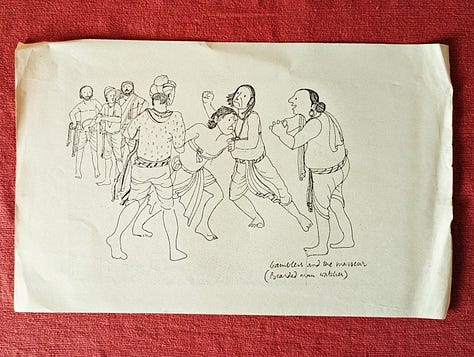

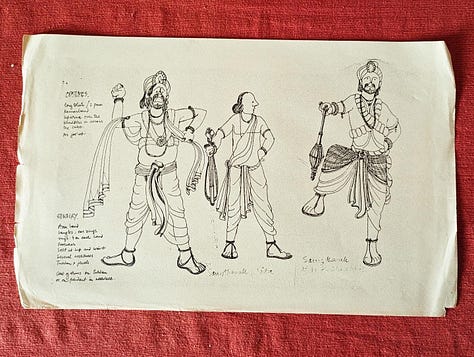

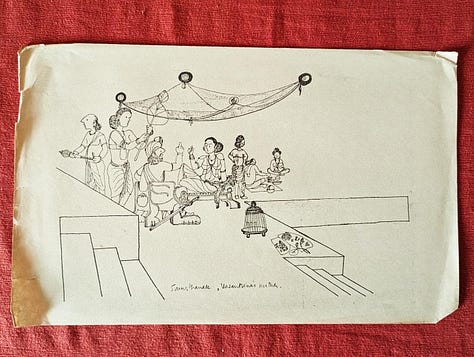

The romance between the poor but handsome young Brahmin, Charudatta, and the moneyed and famed courtesan, Vasantasena, complete with an antagonist in the lecherous brother-in-law of the king, is nestled in an intricate urban setting. To Karnad, Sudraka’s Mricchakatika was, at its core, a play about the city, about urbanity. “No other Indian play, Sanskrit or modern, has caught the pulse of urban life so perfectly, in such a variety of moods,” he wrote.

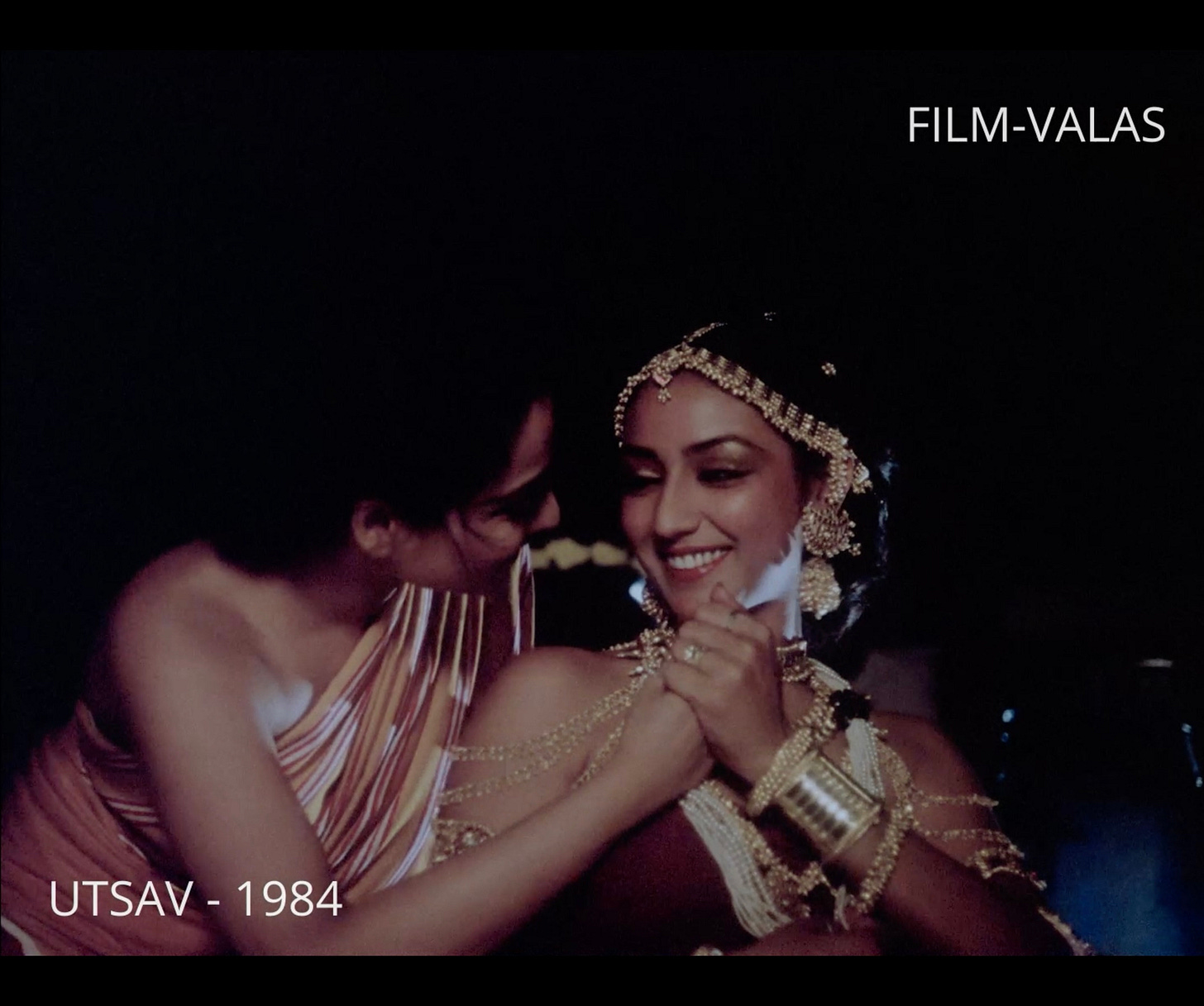

Produced by Shashi Kapoor’s production company, Film-Valas, the film’s casting could very well make for a riveting film of its own. Shashi Kapoor wanted Amitabh Bachchan to play the lecherous comic-villain, Samsthanaka. Karnad was thrilled by the prospect. Before Utsav, Bachchan was shooting for Coolie – but he was seriously injured there, shooting a fight scene, and suffered a splenic rupture. For the country, it left their most beloved hero hovering on the edge of death. For Utsav, it meant Amitabh would not play Samsthanaka. Shashi Kapoor took on the role himself.

A young Kunal Kapoor, “agile and interested in the martial arts”, played Aryaka the rebel, after training at the Gopalan Gurukkal in Madras.

The luminous figure at the centre of the film, playing Vasantasena, was Rekha – then near the height of her stardom. She was “wonderful, disciplined, friendly and responsive to my suggestions,” Karnad writes. But “in point of fact, she was going through a miserable period... and losing Amitabh from the film must have deprived the whole enterprise of its major personal involvement for her.”

Neena Gupta, who played the role of Madanika, Vasantasena’s servant-girl, wrote of working on Utsav in her memoirs, Sach Kahun Toh:

“[The film] didn’t do well at the box office. A lot of people found it too erotically charged and panned it,” she wrote. “But honestly, I think it was a beautiful film that was way ahead of its time. I am really proud to have acted in it, and till date, I think it’s among the best scripts I have ever been a part of.”

In Karnad’s eyes, it was “the streets and the open spaces of the city – the slave market, the public park, the execution site – that dominate[d] the action [in Mricchakatika]… we had to find exteriors as well as interiors that could not only convincingly look as though they were in ancient India, but match each other in their feel and style.” The film, set as it was in ancient India, needed a visual approach that breathed life into a world without electricity; a world illuminated by flames.

Ashok Mehta was enlisted as the director of photography, joining Jayoo and Nachiket Patwardhan, Karnad’s art directors from his Kannada film, Ondanondu Kaladalli. For Karnad, “[t]he unusual visual richness of the film was entirely the creation of Jayoo–Nachiket, aided by Ashok Mehta’s subtle tones.”

He goes on to recollect that:

“Jayoo and Nachiket were ecstatic … they had been given these extraordinary interiors, now their main challenge would be to construct streets and parks that matched them. Ashok Mehta explained to me how he meant to devise a lighting scheme in which the shadows and light evoked an era during which illumination at night was by torches and oil lamps. This joint enthusiasm was the most exhilarating thing about the craftspeople I had working with me. Jayoo, Nachiket and Ashok created a completely believable and yet luminous world with our locations.”

The music, composed by the famed composer duo Laxmikant-Pyarelal, is still recognised today as one of the best in their discography. For Karnad, these “two days stand out for having been an absolute delight – when we recorded the two songs in the film.”

Karnad imagined the lyrics in a very specific kind of Sanskritized vocabulary. He called on Vasant Dev, a professor and poet: “His poems were all written in an ornate, highly romantic ‘Chhayavaadi’ style, with a vocabulary consisting of tropes such as blooming flowers, shimmering moonlight and birdsong.”

On the songs’ vocals, sung by Lata Mangeshkar and Asha Bhonsle, Karnad recalls that when “Asha stumbled during the recording of the first song, she blushed and apologised, saying, ‘It’s such a lovely tune, I forgot myself.’”

Utsav’s distribution and release were a fiasco. It had gone way above budget, due in part to the producer’s idea that it be filmed in parallel in both Hindi and English, for an international market. Still Utsav found its place in cinema history, and in the affections of film-lovers – particularly those with an eye out for transgressive romance.

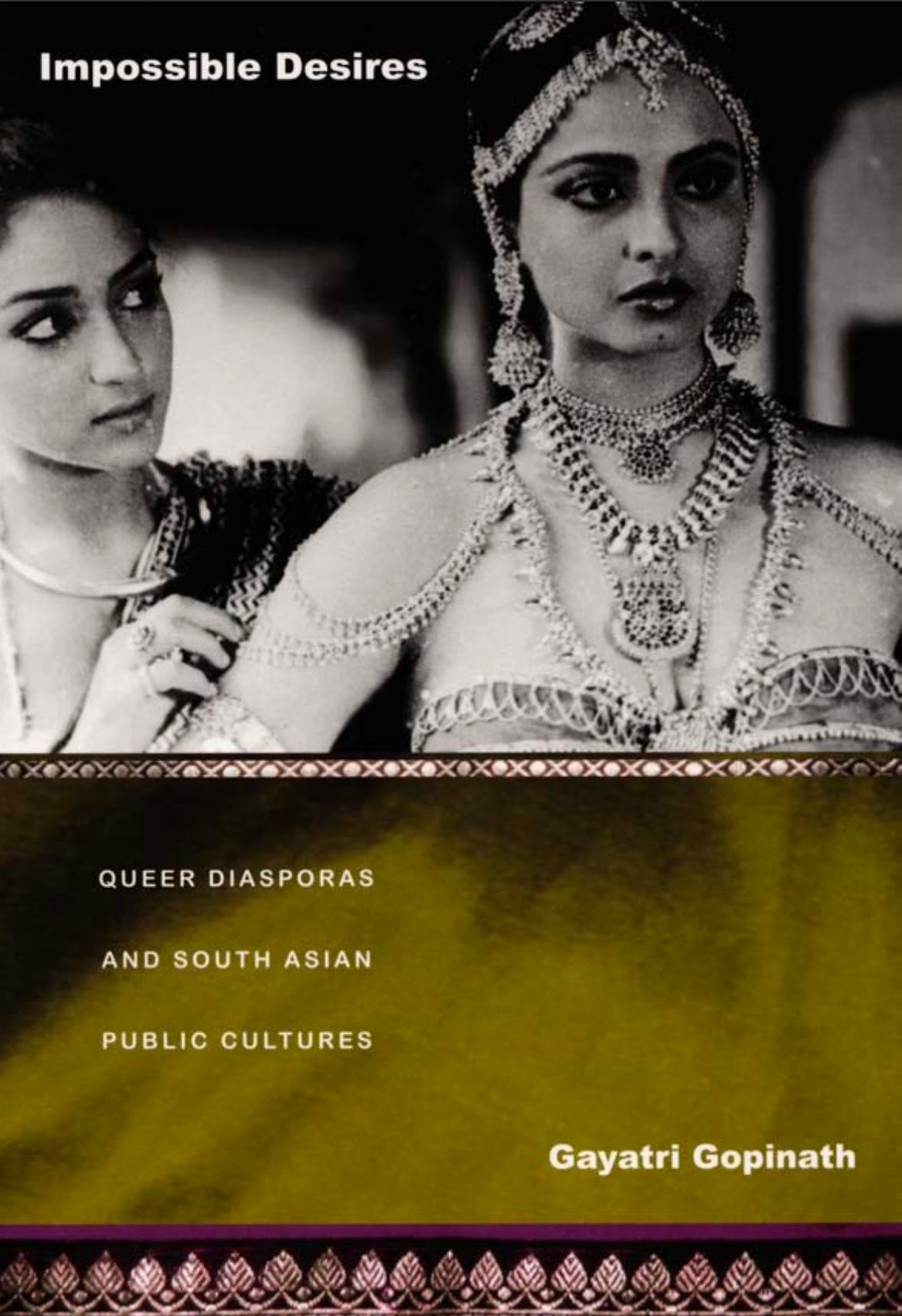

Much has been said, written, and rehashed about Utsav’s eroticism. Gayatri Gopinath, an associate professor at NYU, invites another reading of the film; one that occurred to a lot of us while watching scenes of Vasantasena and Aditi alone.

In her book, Impossible Desires, Gopinath writes:

Utsav reworks the typical love triangle of popular film where two women compete for the man’s attention; here, it is Charudutt who is sidelined while the two women play erotically together. Interestingly, some feminist analyses of the film have critiqued this scene as merely “playing out the ultimate male fantasy,” whereby female bonding between the wife and the courtesan enable the man to “move without guilt between a nurturing wife and a glamourous mistress.”

Clearly such an interpretation misses the more nuanced eroticism between the two women that a queer reading makes apparent. A queer reading might also allow for the possibility of triangulated desire that does not solidify into “lesbian” or “heterosexual,” but rather opens up a third space where both hetero- and homoerotic relations coexist simultaneously.

The scenes of Vasantasena and Aditi together are so loaded, they made the cover of Impossible Desires.

As the critic Sandip Roy remarked to us, “the Rekha - Anooradha Patel scenes out-sizzled the ones with Charudutt himself.”

This newsletter is part of an open archive of Girish Karnad’s life in theatre, film, TV, scholarship and activism. Join us on Instagram and Facebook – and share away if you enjoyed reading this!

Until next time — listen to a series of conversations between Karnad, Arshia Sattar, and Anmol Tikoo: BIC’s The River Has No Fear of Memories.

We’ll see you in your inbox next week with a closer look at Girish Karnad’s relationship with the Mahabharata.